It can be frustrating when you test negative for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) but still suffer from persistent gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. However, the silver lining is that a negative SIBO test rules out one potential cause, bringing us closer to identifying the underlying issue. Before undergoing the SIBO test, you should have completed the test for intestinal methanogen overgrowth (IMO). With SIBO and, IMO ruled out, it’s time to explore other potential diagnoses.

A negative SIBO breath test

According to the North American Consensus guidelines, a rise in hydrogen (≥20 ppm) in a breath test is considered positive for SIBO. If you have followed the preparation guidelines for hydrogen/methane breath testing (HMBT) – such as discontinuing antibiotics, promotility drugs, and laxatives and adhering to the required fasting period – a negative breath test generally means that SIBO is not the cause of your symptoms (1)

If it’s not SIBO, what could it be?

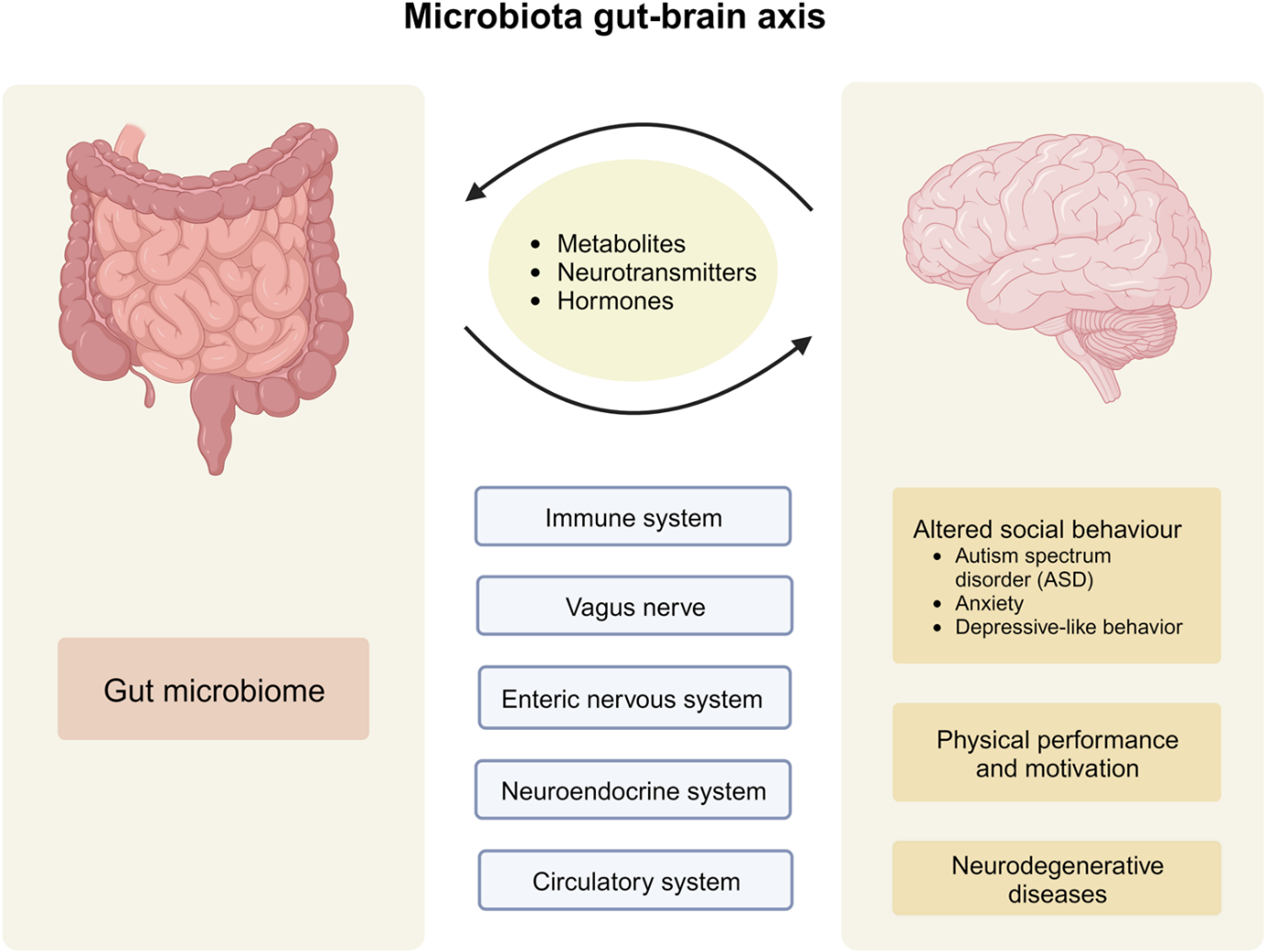

It is now established that there is bidirectional communication between the central nervous system and the extensive network of nerves lining the gut (the enteric nervous system). This is known as the gut-brain axis (GBA), which links the brain’s thoughts and feelings to intestinal function (2). The GBA operates through complex signaling mechanisms that involve neural, immune, and hormone factors. Feeling emotional when you have an upset tummy, knowing the degree of fullness of the stomach, and recognizing the need to open your bowels are examples of the GBA system at work (3). Insights into the GBA axis have also led to the use of antidepressants for relieving GI symptoms, based on the idea that improving mood and reducing psychological distress can relieve gut discomfort (4).

In the last blog, we described the roles of microorganisms residing throughout the GI tract – known as the gut microbiome – and how dysbiosis (an imbalance of beneficial and harmful microorganisms) is implicated in the development of neurological diseases, cancers, and immune deficiencies. Recent advances have confirmed the role of gut microbiota in influencing these gut-brain interactions and how excessive microbiome colonization can lead to disorders of the GBA (2).

There is emerging evidence to suggest that another potential cause of non-specific GI symptoms could be disorders of the GBA, which is estimated to affecting more than 40% of the population. The five most common disorders are irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional dyspepsia (chronic indigestion), functional constipation, functional diarrhea, and functional bloating/distention (5). The term ‘functional’ indicates although patients have ongoing symptoms, standard tests do not find any physical problems. It was once believed that these symptoms have no clear cause, but new understanding of the GBA has changed this perspective (6).

GBA Disorders

The Rome criteria is currently the most widely accepted symptom-based, diagnostic methodology for GBA disorders (7). However, reaching a definitive diagnosis requires thorough history-taking supported by a comprehensive physical examination. Nuances in symptoms – such as onset (sudden vs gradual), duration (acute vs chronic), pain characteristics (location, quality, and continuous vs episodic), and accompanying symptoms (abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, and change in bowel habits) – as well as psychological and social factors that may be symptom-related need to be considered to reach a diagnosis (8).

Figure 1. The microbiota-gut-brain axis is mediated through immune, nervous, and hormonal pathways. Impaired communication between the three parties can lead to disease onset (9).

Treatment of GBA Disorders

It is challenging to outline a treatment plan without a clear diagnosis. However, in this blog, we have grouped GBA disorders based on their predominant symptoms to offer some practical management strategies. The disorders are categorized into diarrhoea-predominant, constipation-predominant, and mixed symptoms.

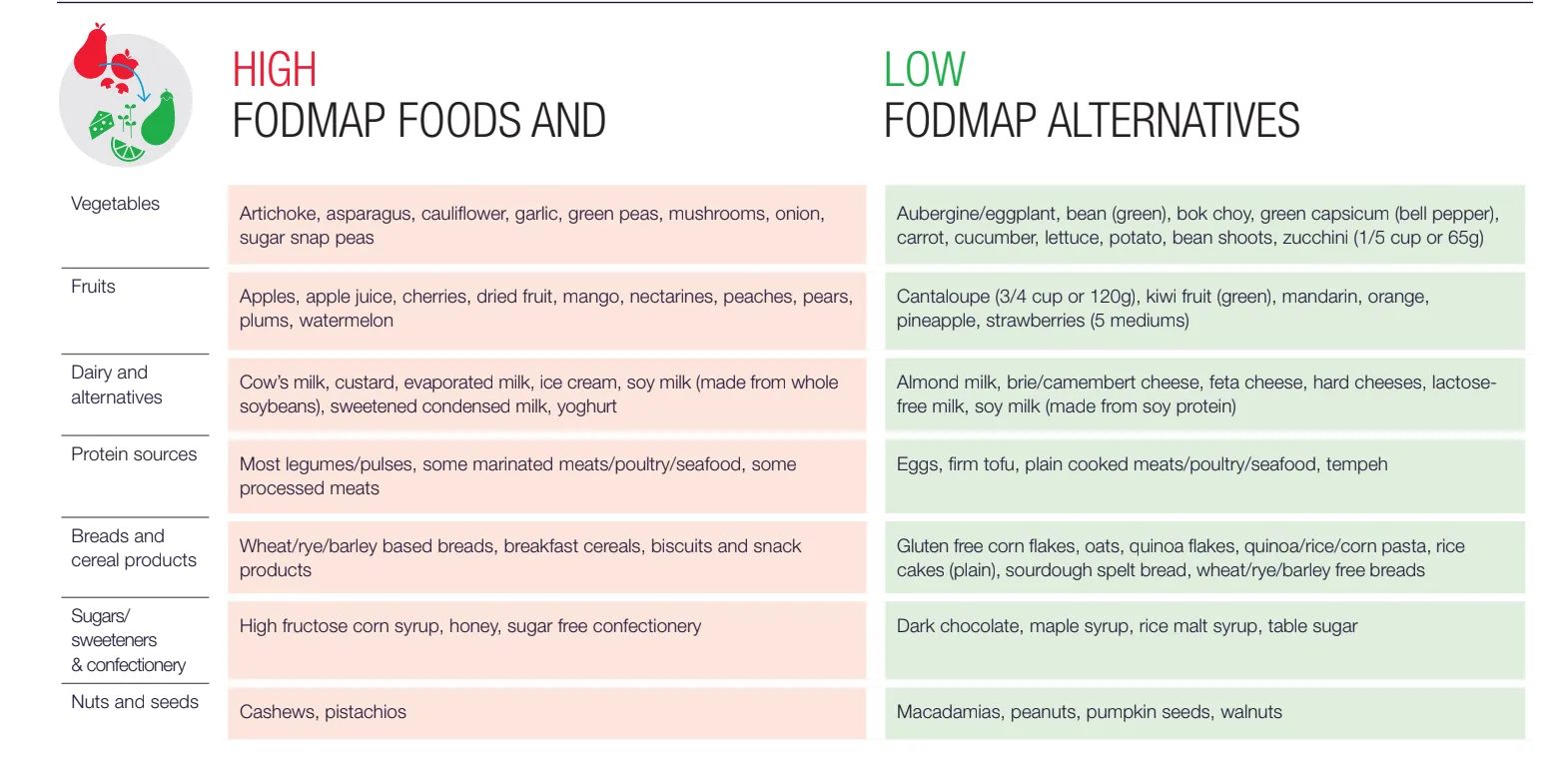

For those experiencing diarrhea-predominant symptoms, implementing a low-FODMAP can promptly and significantly improve diarrhea (10,11). FODMAPs poorly-digested sugars that draw excess liquid into the intestines and promote bacterial fermentation, leading to pressure build-up and diarrhea (12,13) A low-FODMAP diet is also suggested to improve abdominal pain, bloating, and quality of life (14). Figure 2 summarizes foods that are high and low in FODMAP content (11). Following a low-FODMAP diet involves three steps (15).

- Restriction Phase: Adhere to the low-FODMAP diet as closely as possible for 6 weeks to assess its impact on GI symptoms.

- Reintroduction Phase: Gradually reintroduce avoided foods one at a time, in increasing portions, to identify specific carbohydrates that cause symptoms.

- Personalisation phase: Establish a personalized diet plan that includes both low-FODMAP foods and high-FODMAP foods that do not trigger symptoms.

Figure 2. Table of foods with high- and low-FODMAP content (16).

For those experiencing constipation-predominant symptoms, a fiber-rich diet can be effective in alleviating symptoms. Constipation is medically defined as difficult and infrequent bowel movements, typically characterized by having fewer than three bowel movements per week (17). You’ve probably heard that dietary fiber aids in bowel regularity, a fact supported by years of research, but do you know why (18)? First, let’s look into the different types of fiber. There are 2 main categories: soluble fiber (found in the inner flesh of fruits, most root vegetables, and legumes) and insoluble fibers (found in the outer skin of plants) (19). Insoluble fiber increases fecal mass and promotes food passage by stimulating the gut wall and peristalsis (the muscle contractions that propel food through the digestive tract). On the other hand, soluble fiber maintains the water content in stools, making them easier to pass (20). A combination of both fiber types is encouraged to improve constipation symptoms.

For those who do not have consistent bowel habits and struggle with both diarrhea and constipation along with other GI symptoms, treatment can be challenging. Mixed symptoms are multifactorial and there is yet to understand what conditions cause the symptoms to change. Ongoing research aims to uncover the various mechanisms behind changes in gut sensitivity, motility, and microbiome dysbiosis (21). Maintaining general well-being to limit microbiome overgrowth and dysbiosis is key. Patients are advised to:

- Eat regular meals with a healthy, balanced diet and adjust their fiber intake according to their symptoms.

- Maintain adequate fluid intake.

- Engage in 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity at least 5 days a week.

- Identify and manage any stress, depression, or anxiety

If the first-line dietary advice and lifestyle changes are ineffective, patients can consider referral to a clinician for further evaluation. In some cases, patients can be prescribed antimotility drug for persisting diarrhoea, laxatives for constipation or antispasmodic drug for ongoing abdominal pain and spasms (22). Subsequent treatments are also likely to involve multidisciplinary groups with primary physicians, gastroenterologists, and specialist nutritionists.

How can OMED help

We understand that GI symptoms can be distressing and impact your quality of life. It’s important to be patient and give each change time to show results. We recommend implementing one change at a time and allowing it to take effect. The OMED app can assist you in tracking your symptoms and any lifestyle changes to evaluate their effectiveness. Additionally, although you have tested negative for SIBO and IMO, these conditions can flare up, potentially worsening your symptoms. We suggest using the OMED Health Breath Analyzer to regularly monitor your hydrogen levels (used for SIBO diagnosis) and methane levels (used for IMO diagnosis).

References

- Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, Lin H, McCallum R, Rao S, et al. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 May;112(5):775–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.46

- Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol Q Publ Hell Soc Gastroenterol. 2015;28(2):203–9.

- York and Scarborough Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust – Inflammatory Bowel Disease at York Hospital [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.yorkhospitals.nhs.uk/our-services/a-z-of-services/inflammatory-bowel-disease-at-york-hospital/

- Acharekar MV, Guerrero Saldivia SE, Unnikrishnan S, Chavarria YY, Akindele AO, Jalkh AP, et al. A Systematic Review on the Efficacy and Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders: More Control, Less Risk. Cureus. 14(8):e27691. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27691

- Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan;160(1):99-114.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014

- Fikree A, Byrne P. Management of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clin Med. 2021 Jan;21(1):44–52. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0980

- Zhou Q, Verne GN. Are the Rome Criteria a Sound Standard for Gastrointestinal Disorders Worldwide? Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 1;158(5):1212–4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.016

- Tome J, Kamboj AK, Loftus CG. Approach to Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023 Mar 1;98(3):458–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.11.001

- Loh JS, Mak WQ, Tan LKS, Ng CX, Chan HH, Yeow SH, et al. Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024 Feb 16;9(1):1–53. doi: 10.1038/s41392-024-01743-1

- Yoon SR, Lee JH, Lee JH, Na GY, Lee KH, Lee YB, et al. Low-FODMAP formula improves diarrhea and nutritional status in hospitalized patients receiving enteral nutrition: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind clinical trial. Nutr J. 2015 Nov 3;14:116. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0106-0

- Guerreiro MM, Santos Z, Carolino E, Correa J, Cravo M, Augusto F, et al. Effectiveness of Two Dietary Approaches on the Quality of Life and Gastrointestinal Symptoms of Individuals with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2020 Jan 2;9(1):125. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010125

- Healthline [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. FODMAP 101. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/fodmaps-101

- About FODMAPs and IBS | Monash FODMAP – Monash Fodmap [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.monashfodmap.com/about-fodmap-and-ibs/

- Schumann D, Klose P, Lauche R, Dobos G, Langhorst J, Cramer H. Low fermentable, oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyol diet in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition. 2018 Jan 1;45:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2017.07.004

- Gentle low FODMAP diet [Internet]. Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust. [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.kentcht.nhs.uk/leaflet/gentle-low-fodmap-diet/

- Three step FODMAP Diet – Monash Fodmap [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.monashfodmap.com/3_step_fodmap_diet/

- nhs.uk [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Constipation. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/constipation/

- Yang J, Wang HP, Zhou L, Xu CF. Effect of dietary fiber on constipation: a meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Dec 28;18(48):7378–83. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7378

- Akbar A, Shreenath AP. High Fiber Diet. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559033/

- Di Rosa C, Altomare A, Terrigno V, Carbone F, Tack J, Cicala M, et al. Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-C): Effects of Different Nutritional Patterns on Intestinal Dysbiosis and Symptoms. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 28;15(7):1647. doi: 10.3390/nu15071647

- Nee J, Lembo A. Review Article: Current and future treatment approaches for IBS with diarrhoea (IBS-D) and IBS mixed pattern (IBS-M). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Dec;54 Suppl 1:S63–74. doi: 10.1111/apt.16625

- Scenario: Management | Management | Irritable bowel syndrome | CKS | NICE [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 21]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/irritable-bowel-syndrome/management/management/