Receiving an IMO-negative result can be frustrating, especially when persistent gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms continue to affect your quality of life. However, this result is still valuable, as it effectively rules out the overgrowth of methanogens and helps guide further investigations to identify the underlying cause of your symptoms. In previous blogs, we discussed the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment options for those who test positive for IMO. In this blog, we will explain what an IMO-negative result means and outline alternative steps to uncover the true causes of your GI symptoms.

A Negative IMO Test

Assuming no sampling errors or deviations from the established guidelines, hydrogen/methane breath testing (HMBT) serves as a reliable tool for the differential diagnosis of IMO. IMO is characterised by the over-colonisation of methanogenic archaea, predominantly M. smithii, which utilises hydrogen from bacterial fermentation of undigested carbohydrates to produce methane. According to the North American Consensus, a methane level of ≥10 ppm can be considered positive for IMO (1). An IMO-negative result is therefore likely to indicate a less serious issue and allows for more focused exploration to uncover the causes of persistent GI symptoms.

What else could it be? – SIBO

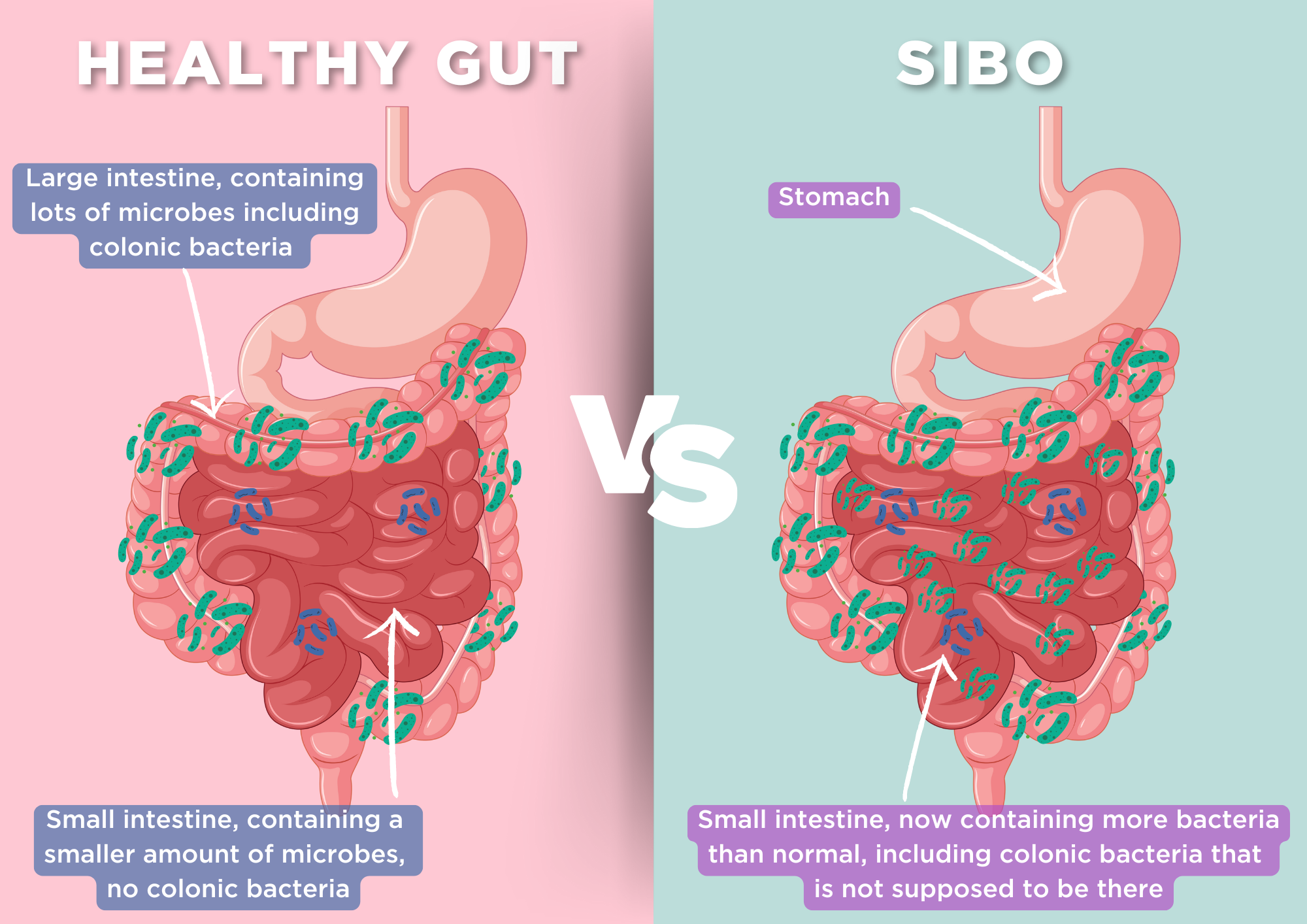

Another potential aetiology of non-specific GI symptoms is small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), which is also underpinned by an overgrowth of microorganisms in the gut. Like IMO, SIBO can be diagnosed using breath testing, with a positive result indicated by a hydrogen level of ≥20 ppm above baseline (1). However, important differences exist between SIBO and IMO (1):

- In SIBO, the most common species identified are Escherichia coli, Aeromonas, and Klebsiella, rather than M. smithii (3).

- SIBO is characterised by excessive bacterial growth exclusively in the small intestine, whereas methanogens, as indicated by breath tests and stool samples, can be present throughout the entire gut.

- SIBO is more often associated with diarrhoeal symptoms, whereas IMO is more commonly linked to constipation.

Normally, bacterial growth in the small intestine is limited by the presence of stomach acid, bile, peristalsis, proteolytic digestive enzymes, intact ileocecal valve and secretory IgA. However, certain conditions can foster the growth of invasive strains of bacteria, leading to damage to the epithelial cell layer and resulting in GI symptoms (3). The aetiologies and risk factors for these symptoms may include (4):

| Gut dysmotility | Diabetes mellitus, connective tissue disorders (eg: systemic sclerosis), medications (opioids, anticholinergics) |

| Altered GI Secretions | Medications (proton pump inhibitors), chronic pancreatitis |

| Anatomical Alterations | Ileocecal valve impairment, small bowel diverticular disease, roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

| Impaired Immunity | Combined variable immunodeficiency, hypogammaglobulinemia |

In most cases, SIBO presents with a range of non-specific symptoms, including bloating, abdominal pain, changes in bowel movements, flatulence, and unintended weight loss. In more extreme causes, SIBO can lead to malnutrition, vitamin B12 deficiency and osteoporosis (5).

Reversing the pathophysiology that predispose individuals to SIBO is often challenging. As a result, management typically focuses on limiting bacterial overgrowth and addressing the complications of SIBO. This can be achieved through dietary interventions (e.g. Low FODMAP diet), directed antimicrobial therapy (e.g. herbal antimicrobials or antibiotic and correction of micronutrient deficiencies, (6).

What else could it be? – Disorders of the gut-brain axis (GBA)

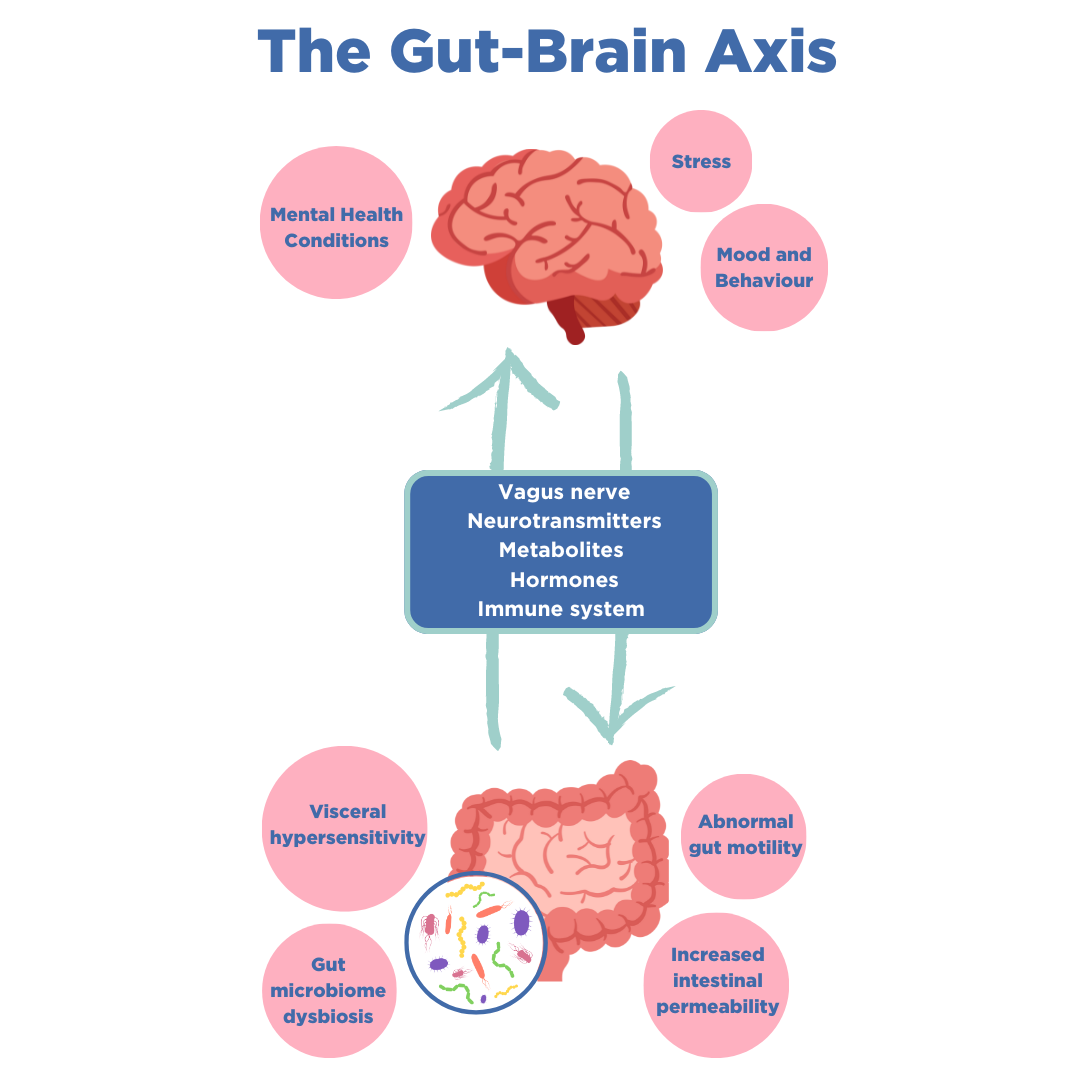

Following a negative diagnosis of SIBO, the next step is to consider conditions that may involve impaired communication between the intestines and the central nervous system (CNS). It is now established that bidirectional communication links the brain’s cognitive and emotional centres with peripheral intestinal functions, known as the gut-brain axis. The GBA operates through complex signalling mechanisms that involve neural, immune and hormone mediators (7).

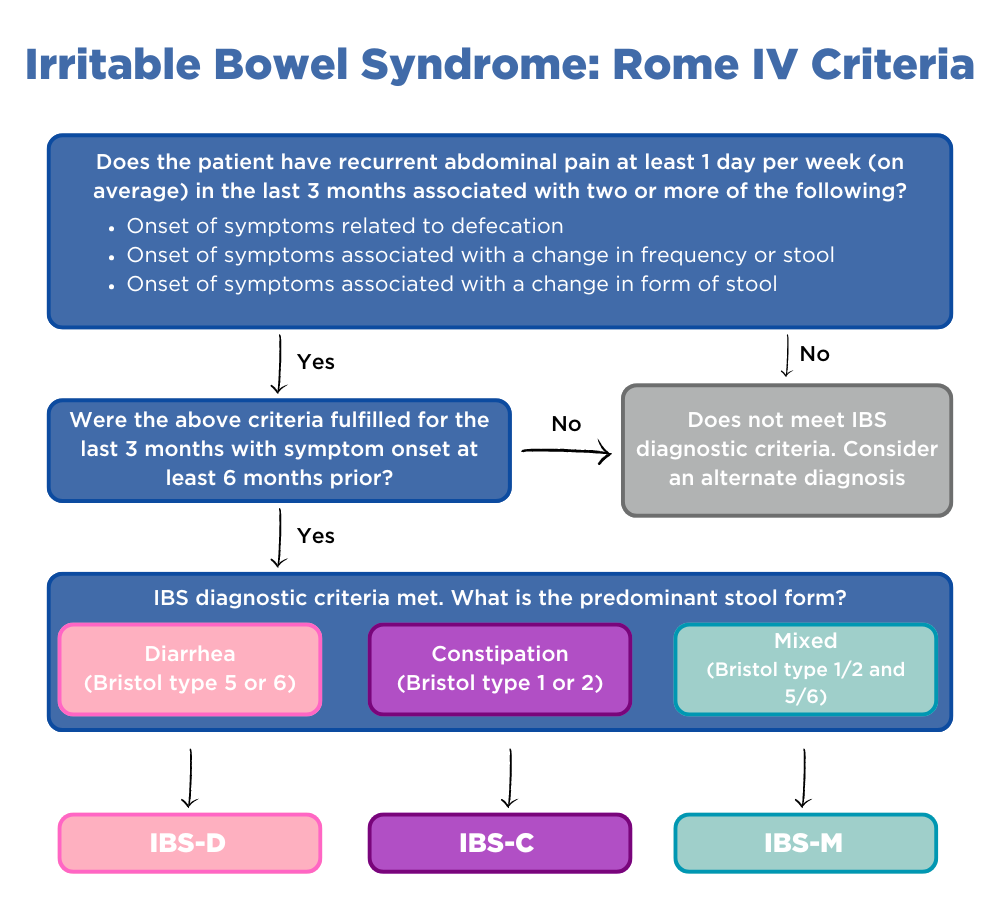

Disorders of the gut-brain axis, formally known as functional gastrointestinal disorders, affect 40% of the population worldwide (8, 9). These disorders can lead to motility disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, altered mucosal and immune function, altered gut microbiome, and impaired CNS processing. Common GBA disorders include IBS, functional dyspepsia, functional constipation, functional diarrhoea and functional bloating/ distention (10).

The Rome criteria is currently the most widely accepted symptom-based, diagnostic methodology for GBA disorders (11). However, reaching a definitive diagnosis requires a thorough history-taking supported by a comprehensive physical examination. The nuances of symptoms—such as onset (sudden vs. gradual), duration (acute vs. chronic), pain characteristics (location, quality, continuous vs. episodic), and accompanying symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, nausea, bloating, changes in bowel habits)—may influence the diagnosis. Additionally, psychosocial factors should be considered to provide a well-rounded assessment within the bio-psycho-social model.

As such, treatments can be complex and may require a multidisciplinary team. It is not advisable to start antimicrobial therapy or restrictive diets without a clear diagnosis or support from healthcare professionals, due to the associated risks. However, we have grouped GBA disorders according to their predominant symptoms to offer some practical management strategies.

For patients experiencing diarrhoea-predominant symptoms: implementing a low-FODMAP diet may provide prompt and significant relief. This dietary intervention restricts the intake of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), which are carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed and difficult to digest. FODMAPs draw excess liquid into the intestinal lumen and are fermented by gut bacteria, leading to pressure buildup and diarrhoea (12).

Foods high in FODMAP include cereal grains (wheat, rye and barley), certain fruits (apples, pear and watermelon) and certain dairy products (milk, yoghurt and ice cream). Foods low in FODMAP include rice, oats, certain fruits (banana, blueberry, orange) as well as most nuts and seeds (13).

For patients experiencing constipation-predominant symptoms, dietary fibre intake can increase stool frequency (14). Insoluble fibre increases faecal mass and colonic transit rate by inducing secretion and peristalsis. Soluble fibre normalises stool form with its high gel-forming capacity. A combination of both fibre types has been shown to improve constipation symptoms.

For patients with inconsistent bowel habits, treatment can be challenging. Mixed symptoms are multifactorial, and the conditions causing these fluctuations are not yet fully understood. Ongoing research aims to elucidate the mechanisms behind changes in gut sensitivity, motility, and microbiome dysbiosis. Maintaining overall well-being to prevent microbiome overgrowth and dysbiosis is crucial. This involves maintaining a balanced diet, adopting a healthy lifestyle, and supporting mental well-being (15).

The management of gut diseases should be individualised according to each person’s symptoms and psychosocial context. Although these methods are supported by research, they may not be effective for everyone. If these strategies prove inadequate, consulting a specialist is the next step. Treatment options may then include antimotility drugs for persistent diarrhoea, laxatives for constipation, and antispasmodic drugs for ongoing abdominal pain or spasms.

Conclusion

We understand that testing negative for IMO can be frustrating, as it means the underlying cause of your GI symptoms remains unidentified. However, OMED is here to assist you. We recommend using the OMED Health Breath Analyzer to check for SIBO. If the result is negative, exploring whether you have a disorder of the gut-brain axis (GBA) is the next step.

It’s important to note that SIBO and IMO are conditions that can flare up unexpectedly. If you are prone to GI symptoms, we suggest obtaining the OMED device as it allows for repeated use and long-term monitoring. This device is used in conjunction with an app, where you can log any symptoms or changes in dietary intake, providing you with a more comprehensive understanding of your condition.

References

- Rezaie A, Buresi M, Lembo A, Lin H, McCallum R, Rao S, et al. Hydrogen and Methane-Based Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Disorders: The North American Consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 May;112(5):775–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.46

- Pimentel M, Saad RJ, Long MD, Rao SSC. ACG Clinical Guideline: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG. 2020 Feb;115(2):165. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000501

- Sorathia SJ, Chippa V, Rivas JM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546634/

- Ahmed JF, Padam P, Ruban A. Aetiology, diagnosis and management of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar 1;14(2):149–54. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2022-102163

- Cleveland Clinic [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 5]. SIBO: Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21820-small-intestinal-bacterial-overgrowth-sibo

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Management – UpToDate [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/small-intestinal-bacterial-overgrowth-management#H153040933

- Carabotti M, Scirocco A, Maselli MA, Severi C. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(2):203–9. PMID: 25830558

- Wei L, Singh R, Ro S, Ghoshal UC. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH Open. 2021 Mar 23;5(9):976–87. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12528

- Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021 Jan 1;160(1):99-114.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.014

- Zhou Q, Verne GN. Are the Rome Criteria a Sound Standard for Gastrointestinal Disorders Worldwide? Gastroenterology. 2020 Apr 1;158(5):1212–4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.016

- Gastroenterology Consultants of San Antonio [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Low FODMAP Diet for Irritable Bowel Syndrome | IBS Treatment. Available from: https://www.gastroconsa.com/patient-education/irritable-bowel-syndrome/low-fodmap-diet/

- nhs.uk [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – Further help and support. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs/further-help-and-support/

- Yang J, Wang HP, Zhou L, Xu CF. Effect of dietary fiber on constipation: a meta analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Dec 28;18(48):7378–83. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7378

- Di Rosa C, Altomare A, Terrigno V, Carbone F, Tack J, Cicala M, et al. Constipation-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-C): Effects of Different Nutritional Patterns on Intestinal Dysbiosis and Symptoms. Nutrients. 2023 Mar 28;15(7):1647. doi: 10.3390/nu15071647

- Scenario: Management | Management | Irritable bowel syndrome | CKS | NICE [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/irritable-bowel-syndrome/management/management/