Congratulations on taking the first step towards better digestive health! You’ve just received a positive result for SIBO. Could this be the cause behind the flatulence (gas), abdominal distention, pain, and other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms you’ve been experiencing?

The Importance of Gut Microbiome

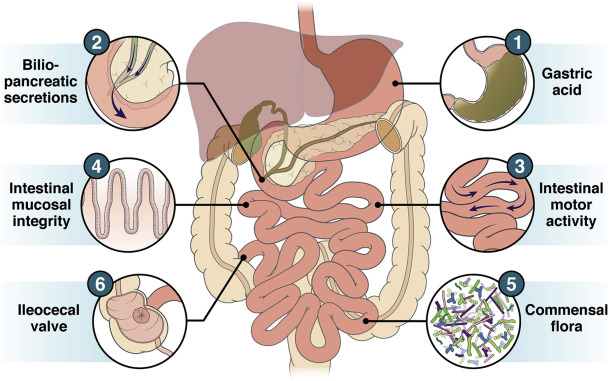

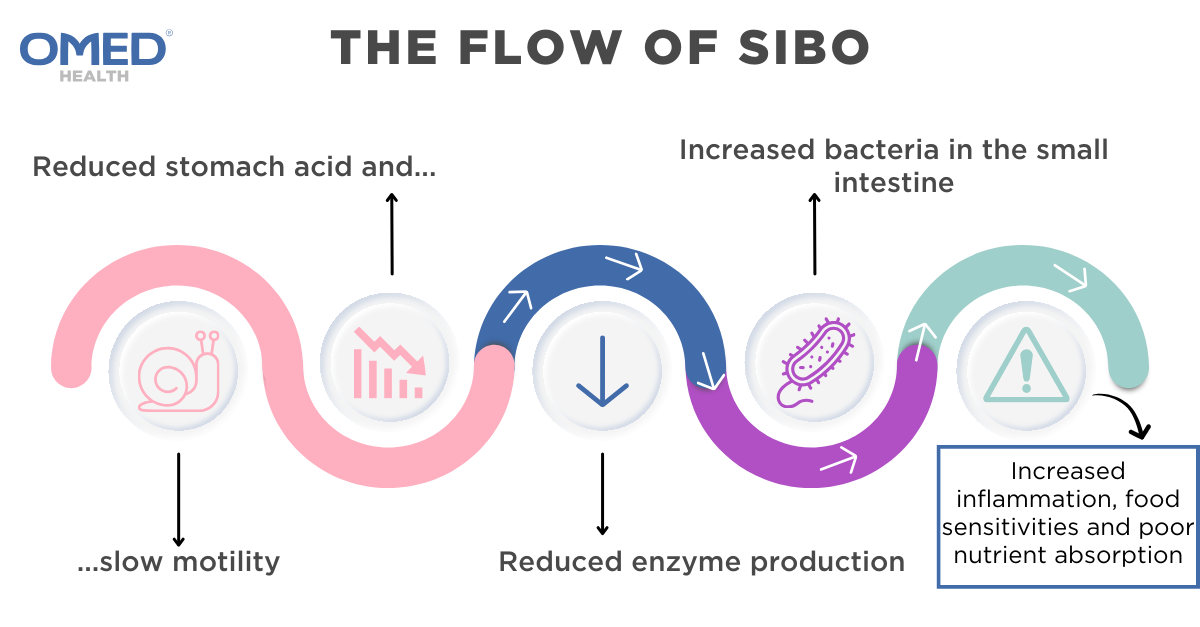

Although it may seem counterintuitive, it is estimated that the number of bacterial cells in our body is roughly equal to the number of human cells (1). In the small intestine, overgrowth of microorganisms is normally limited by factors such as gut motility and stomach acid. In areas further down the digestive tract, such as the colon, the density of microorganisms increases and their composition also varies. When the gut microbiome is maintained in a delicate balance with the host (a state known as eubiosis), it performs important functions such as supporting fiber digestion, infection defence and facilitating nutrient absorption. In the case of an imbalance (dysbiosis), people can become more susceptible to certain diseases and can experience uncomfortable digestive health symptoms. An imbalanced gut microbiome has been linked to the development of cancers, type 2 diabetes, hepatic steatosis, and neurological disorders (3,4).

Figure 1. Factors that protect against the development of SIBO, which may be susceptible to disruptions when diseases develop (5).

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

SIBO is characterised by an over-colonisation of bacteria in the small intestine, which arises when a person’s balance is compromised. As hydrogen gas is exclusively produced by microorganisms in the gut, not by human cells, an elevated hydrogen level in the hydrogen/methane breath testing (HMBT) is indicative of increased bacterial growth (6). Microbiome overgrowth can result from changes in gut motility (eg: irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), narcotic use and diabetes mellitus), anatomical disorders (eg: small intestinal diverticulosis and blind intestinal loops), decreased stomach acid production (due to the use of proton pump inhibitors) and immune disorders (eg: HIV) (7,8).

Before the characterization of SIBO, many cases were misdiagnosed as IBS, due to the overlap in their symptoms. However, studies have shown that they can co-exist, with 36.4%-78% of IBS patients also having SIBO (9,10).

| Signs and symptoms | Pathophysiology – what is causing them and how do they manifest? |

| Bloating and distension | Normally, food mixes with stomach acid and moves along the small intestine to the large intestine. However, when food passage through the small intestine becomes stalled, bacteria from the large intestine can migrate upwards and ferment the undigested carbohydrates. This produces gas that stretches the small intestine, causing the patient to feel bloated. Over time, bloating may culminate in abdominal distension, where your abdomen noticeably increases in size. |

| Flatulence | The overabundance of bacteria in the small intestine, coupled with a greater access to carbohydrates, can lead to excess gas production. Bacterial fermentation produces hydrogen gas, which can be utilized by other microbes in the intestines known as archaea to produce methane. |

| Diarrhea | Increased gas production and inflammatory responses associated with SIBO can cause loose stools. |

| Abdominal pain and cramps | Most patients with SIBO experience colic abdominal pain, caused by intestinal issues like diarrhoea / constipation, characterised by abdominal pain that comes and goes; some patients experience abdominal stitches, due to excess bacterial-associated gas production, which is a slightly sharper pain (11) |

| Malabsorption and weight loss | The disruption to the normal functioning of the small intestine can cause nutrient absorption (carbohydrates, proteins, fats, water, vitamins and minerals) to be impaired. |

| Vitamin deficiency | In more extreme cases, untreated SIBO can lead to nutrient deficiency, vitamin deficiency, osteoporosis, kidney stones and dehydration. |

Next steps

The good news is that the symptoms of SIBO can be effectively addressed. Currently, there are 3 main treatment pathways:

- Low FODMAP Diet + Antimicrobials

- Low FODMAP Diet + Antibiotics

- Elemental diet

| Treatment | Aim | Research Evidence |

| A low-FODMAP diet | Alleviate symptoms | A low-FODMAP diet is one that refrains from carbohydrates which are hard to digest, depriving bacteria of the energy sources needed for their growth and reproduction (16). As less fermentation occurs, less gases are produced and less GI symptoms present. Foods high in FODMAP include cereal grains (wheat, rye and barley), certain fruits (apples, pear and watermelon) and certain dairy products (milk, yoghurt and ice cream). Foods low in FODMAP include rice, oats, certain fruits (banana, blueberry, orange) as well as most nuts and seeds (17). |

| Antimicrobials

|

Bacterial eradication + alleviation of symptoms | Herbal antimicrobials can be used to treat SIBO to try and avoid the overuse of antibiotics, and to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance. This includes probiotics and herbal remedies that include ginger and peppermint, which have been shown to be effective alternative SIBO treatments in some patients. |

| Antibiotics | Bacterial eradication + alleviation of symptoms | Bactericidal antibiotics are specifically targeted to kill bacteria. Rifaximin is an established first-line treatment to combat hydrogen-predominant bacterial overgrowth (12). It differentiates from other antibiotics as it can eliminate a broad array of intestinal pathogens. In addition, it is poorly absorbed, meaning that it is unlikely to exert systemic side effects (13). However, successful long-term management of SIBO should incorporate other strategies to limit recurrence as well as avoid antibiotic resistance. |

| Elemental diet | Alleviation of symptoms | The elemental diet is an allergen-free formula that serves as a complete source of nutrition, including vitamins and minerals (14). As the solution can be absorbed by the upper parts of the small intestine without active digestion, it reduces the likelihood of microbial fermentation of any undigested carbohydrates. Elemental diet is especially helpful in patients who have malnutrition. Although an elemental diet can effectively improve SIBO, it is often associated with poor compliance due to its poor palatability and restrictive nature (15). |

Conclusion

Maintaining a nutritious, well-balanced diet is paramount to retaining gut health. Whilst it might be tempting to try all the methods mentioned above, they must be done in moderation, and under the guidance of a healthcare professional. An imbalanced diet can lead to malnutrition, adversely affect your health, and even exacerbate your GI symptoms. Foods high in FODMAP include fruits and vegetables that are important for your diet, hence, it is crucial to remove and reintroduce them to your diet one by one, to effectively identify the cause of your symptoms, but also identify alternatives and levels of tolerance that allow you to maintain a varied diet. Although antibiotics can rapidly eradicate bacterial overgrowth, their use is limited by contraindications and the risk of developing antibiotic resistance. For this reason, antimicrobials such as herbal therapies should be used first when possible.

SIBO can recur after treatment. Adherence to your treatment regime and follow-up appointments with healthcare professionals are key to preventing relapse and ensuring long-term management of the condition.

OMED is here for you

The OMED Health Breath Analyzer is a cost-effective, reusable solution designed to measure hydrogen and methane levels in a home setting. When used in conjunction with the OMED Health App, which tracks your symptoms and diet, you can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the potential causes of your symptoms. SIBO is an uncomfortable condition affecting many individuals. If you suspect that you may have SIBO, ordering the OMED Health Breath Analyzer is a good starting point. In the UK, you can use it to get diagnosed as well as monitor your hydrogen and methane levels in the long run. Does this sound of interest to you? Visit the OMED Health Store and start your journey to improved gut health today.

References

- Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body. PLoS Biol. 2016 Aug 19;14(8):e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533

- Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D, Xiao C, et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Apr 23;7(1):1–28. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00974-4

- Hills RD, Pontefract BA, Mishcon HR, Black CA, Sutton SC, Theberge CR. Gut Microbiome: Profound Implications for Diet and Disease. Nutrients. 2019 Jul 16;11(7):1613. doi: 10.3390/nu11071613

- Jiang C, Li G, Huang P, Liu Z, Zhao B. The Gut Microbiota and Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2017;58(1):1–15. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161141

- Bushyhead D, Quigley EMM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth-Pathophysiology and Its Implications for Definition and Management. Gastroenterology. 2022 Sep;163(3):593–607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.002

- Pitcher CK, Farmer AD, Haworth JJ, Treadway S, Hobson AR. Performance and Interpretation of Hydrogen and Methane Breath Testing Impact of North American Consensus Guidelines. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Dec;67(12):5571–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07487-8

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis – UpToDate [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/small-intestinal-bacterial-overgrowth-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis?search=Small%20intestinal%20bacterial%20overgrowth&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2%7E149&usage_type=default&display_rank=2

- Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Feb;3(2):112–22.

- Onana Ndong P, Boutallaka H, Marine‐Barjoan E, Ouizeman D, Mroue R, Anty R, et al. Prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): Correlating H2 or CH4 production with severity of IBS. JGH Open Open Access J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Apr 3;7(4):311–20. doi: 10.1002/jgh3.12899

- Ghoshal UC, Shukla R, Ghoshal U. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Bridge between Functional Organic Dichotomy. Gut Liver. 2017 Mar 15;11(2):196–208. doi: 10.5009/gnl16126

- amelia.bishop. What causes a stitch and how to stop it [Internet]. Carl Todd Clinic. 2022 [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: https://thecarltoddclinic.com/insights/what-causes-a-stitch-and-how-to-stop-it/

- Sorathia SJ, Chippa V, Rivas JM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546634/

- Koo HL, DuPont HL. Rifaximin: A Unique Gastrointestinal-Selective Antibiotic for Enteric Diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010 Jan;26(1):17–25. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333dc8d

- Nasser J, Mehravar S, Pimentel M, Lim J, Mathur R, Boustany A, et al. Elemental Diet as a Therapeutic Modality: A Comprehensive Review. Dig Dis Sci [Internet]. 2024 Jul 13 [cited 2024 Aug 20]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-024-08543-1doi: 10.1007/s10620-024-08543-1

- Rao SSC, Bhagatwala J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019 Oct 3;10(10):e00078. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000078

- Syed K, Iswara K. Low-FODMAP Diet. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562224/

- Gentle low FODMAP diet [Internet]. Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust. [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.kentcht.nhs.uk/leaflet/gentle-low-fodmap-diet/

- Habishi AE, McLaughlin J, Johns W, Leitao E, Paine P. PWE-047 Metronidazole is A Less Effective Therapy for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Gut. 2016 Jun 1;65(Suppl 1):A162–A162. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312388.293