The Gut-Brain Axis

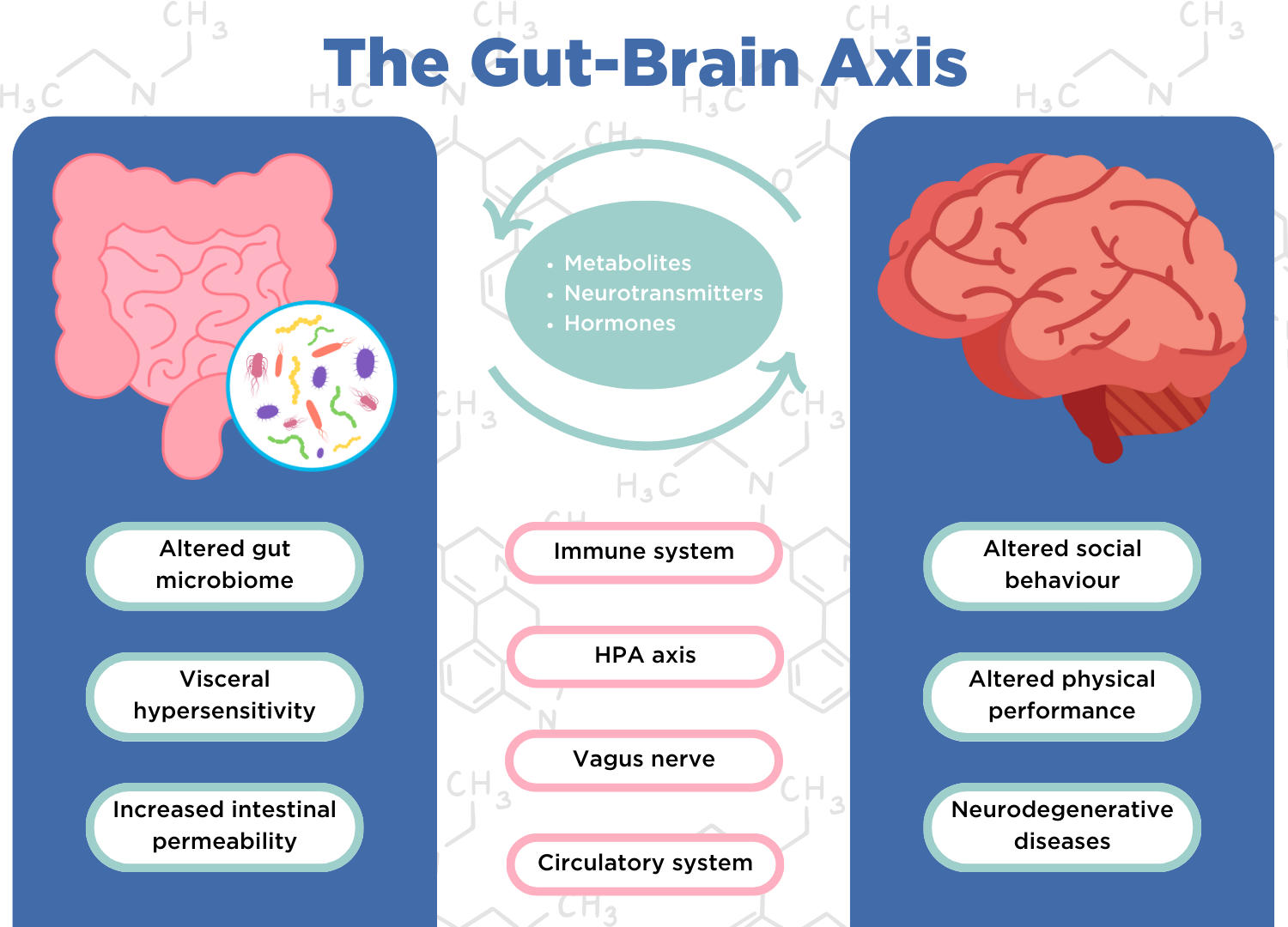

Is there a relationship between the gut and the brain? The bidirectional communication between the brain and the gut is known as the gut-brain axis. Bidirectional means that whilst the gut can affect the brain, the brain can also affect the gut. This connection is a dynamic system, in which the gut microbiome plays a key role. The mechanisms by which our gut communicates with and influences the central nervous system happen via influencing the nerves which can impact the sensation of pain and alter muscle contractions, hormone signaling, and altered immune responses.

Does stress start in the gut? It is thought that this connection could explain why gut symptoms are often reported in psychiatric illnesses, such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease (1-5).

The gut is affected by our stress response, also known as the fight-or-flight response. When we become stressed and trigger our fight-or-flight response, digestion can slow down or even stop. This is so the body can divert all its internal energy to facing the ‘threat’ that is making us stressed. This is also why when we feel nervous, such as performing public speaking, the digestive process may also slow down or be temporarily disrupted, causing gut symptoms such as abdominal pain (6).

This could help to explain why stress and stomach problems go hand in hand (7). Our gut can also influence the immune system and may be linked to the immune dysfunction that is seen in depression and schizophrenia (7).

A key component to the functioning of the human gut is the large collection of microorganisms living there, called the gut microbiome. The gut microbiome consists mainly of bacteria but also includes viruses, fungi, protozoa, and archaea. The collective genes of these bacterial cells are more than the amount of human DNA present in the body. We have over 100 bacterial genes for every human gene! Given this genetic potential of the gut microbiome, it’s not surprising that the gut appears to play a role in many physiological processes in the human body (7), including the gut-brain axis. This three-way connection is also known as the gut-microbiota-brain axis.

How the mind can affect the gut

Gastroenterologists (gut doctors) are no strangers to the gut-brain axis. Mood disturbances, anxiety, and stress are all recognized as playing a role in many different functional gut disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and other gut conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Many people with functional gut disorders are thought to perceive pain more strongly than other people do. This is known as visceral hypersensitivity. This is because their brains are thought to be more responsive to pain signals from the gut. However, it isn’t clear to what extent differences in muscle function in these patients (such as cramps) are causing the pain, and to what extent visceral hypersensitivity is amplifying this.

Stress can make the existing pain seem even worse and is increasingly being recognized as an important factor in the pathophysiology of many gut conditions. Studies have shown that both chronic and acute psychological stress can alter the composition of the gut microbiome. For example, one study found that catecholamines (chemicals that are released during a stress response) can elevate certain bacterial levels, such as Escherichia coli, 10,000-fold (8). These species may overcrowd the beneficial species in the gut, leading to gut microbiome dysbiosis (9).

Stress can also increase intestinal permeability which could allow for certain metabolites produced by the gut microbiome that do not normally exit the intestinal wall to enter the blood and circulate through the body (10), triggering processes such as inflammation. When stressed, cortisol (a steroid hormone) is produced and released into your bloodstream. A study found that those with elevated cortisol in their blood had increased intestinal permeability (11).

Therefore, some patients with functional gut conditions might improve with treatments or therapy to reduce stress or treat anxiety or depression. Studies have shown that psychologically based approaches can lead to an improvement in digestive symptoms (12).

Could your gut problems – such as abdominal pain or diarrhea – be related to stress? Discuss this with your doctor, and together you can come up with strategies to help you deal with the stressors in your life and ease your digestive discomforts.

How can OMED Health help?

If you are unsure what’s causing your gut health issues, we recommend trying our comprehensive Gut Reset+ plan which includes breath testing, doctor’s advice, personalized data analysis treatments and gut recovery supplements.

The OMED Health App allows you to track your mental well-being alongside your physical gut health symptoms to help identify whether there are connections between them. Our Breath Analyzer can provide insights into the possible influences of the gut microbiome by recording hydrogen and methane levels in the breath. Hydrogen and methane levels are important indicators for the state of your gut microbiome, and these measurements are relayed directly to the app. This means that all the data relating to the state of your gut microbiome, stress levels, and physical symptoms can be stored in one convenient place.

By analyzing the data collected alongside the help of an expert, we can explore if there is a possible connection between stress and your gut health. This can inform you of potential triggers of your symptoms. Using our platform, you can use this information to make well-informed decisions about the best treatment options available to you, to ensure the highest chance of successfully managing your symptoms.

References

- Privitera GJ, Misenheimer ML, Doraiswamy PM. From weight loss to weight gain: appetite changes in major depressive disorder as a mirror into brain-environment interactions. Front Psychol. 2013 Nov 21;4:873. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00873

- Mussell M, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Herzog W, Löwe B. Gastrointestinal symptoms in primary care: prevalence and association with depression and anxiety. J Psychosom Res. 2008 Jun;64(6):605–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.019

- McElhanon BO, McCracken C, Karpen S, Sharp WG. Gastrointestinal symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014 May;133(5):872–83. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-3995

- Severance EG, Prandovszky E, Castiglione J, Yolken RH. Gastroenterology issues in schizophrenia: why the gut matters. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015 May;17(5):27. DOI: 10.1007/s11920-015-0574-0

- Edwards L, Quigley EM, Hofman R, Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal symptoms in Parkinson disease: 18-month follow-up study. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc. 1993;8(1):83–6. DOI: 10.1002/mds.870080115

- Harvard Health [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2024 May 7]. Stress and The Sensitive Gut – Harvard Health Publishing. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/stress-and-the-sensitive-gut

- Butler MI, Mörkl S, Sandhu KV, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. The Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: What Should We Tell Our Patients?: Le microbiote Intestinal et la Santé Mentale : que Devrions-Nous dire à nos Patients? Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2019 Nov;64(11):747–60. DOI: 10.1177/0706743719874168

- Madison A, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress, depression, diet, and the gut microbiota: human–bacteria interactions at the core of psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2019 Aug;28:105–10. DOI: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.01.011

- Freestone PP, Williams PH, Haigh RD, Maggs AF, Neal CP, Lyte M. Growth stimulation of intestinal commensal Escherichia coli by catecholamines: a possible contributory factor in trauma-induced sepsis. Shock Augusta Ga. 2002 Nov;18(5):465–70. DOI: 10.1097/00024382-200211000-00014

- Malan-Muller S, Valles-Colomer M, Raes J, Lowry CA, Seedat S, Hemmings SMJ. The Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: Implications for Anxiety- and Trauma-Related Disorders. Omics J Integr Biol. 2018 Feb;22(2):90–107. DOI: 10.1089/omi.2017.0077

- Vanuytsel T, van Wanrooy S, Vanheel H, Vanormelingen C, Verschueren S, Houben E, et al. Psychological stress and corticotropin-releasing hormone increase intestinal permeability in humans by a mast cell-dependent mechanism. Gut. 2014 Aug;63(8):1293–9. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305690

- Harvard Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 May 1]. The gut-brain connection. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/the-gut-brain-connection