You may have heard that exercise can be a good way to improve your gut health. But do you need to get out of breath to enjoy the benefits of exercise? Less intense activities like yoga, walking, and meditation may offer unique benefits for digestion without the strain of high-intensity workouts. In fact, whilst intense exercise can improve cardiovascular fitness and endurance, it can also stress the body, leading to gut discomfort (1). Therefore, lower-intensity exercises may provide the best of both worlds. In this blog, we sift through the research to find out whether yoga really does improve our digestive health and why.

According to the scientific literature, there is a general consensus that yoga is a safe activity for people with gastrointestinal disorders and it may have positive effects on reducing gut symptom severity (2). However, the evidence is not clear-cut, and more work needs to be done to find direct correlations between specific yoga flows and improved physiological outcomes. What we do know, is why yoga could be helpful for people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It’s all to do with the gut-brain axis which we will explain in due course.

First, try this: take three big breaths, and each time, try breathing out for longer than before. Do you feel any different? Just a few deep breaths may be enough to kick start our parasympathetic nervous system to help us relax (3). The parasympathetic nervous system is often called the ‘rest and digest’ system because it regulates how fast our hearts beat and whether to direct oxygenated blood to the gut to aid digestion. This is why we sometimes feel sleepy after a big meal – our body needs to expend energy to digest our food, allowing the rest of the body to relax.

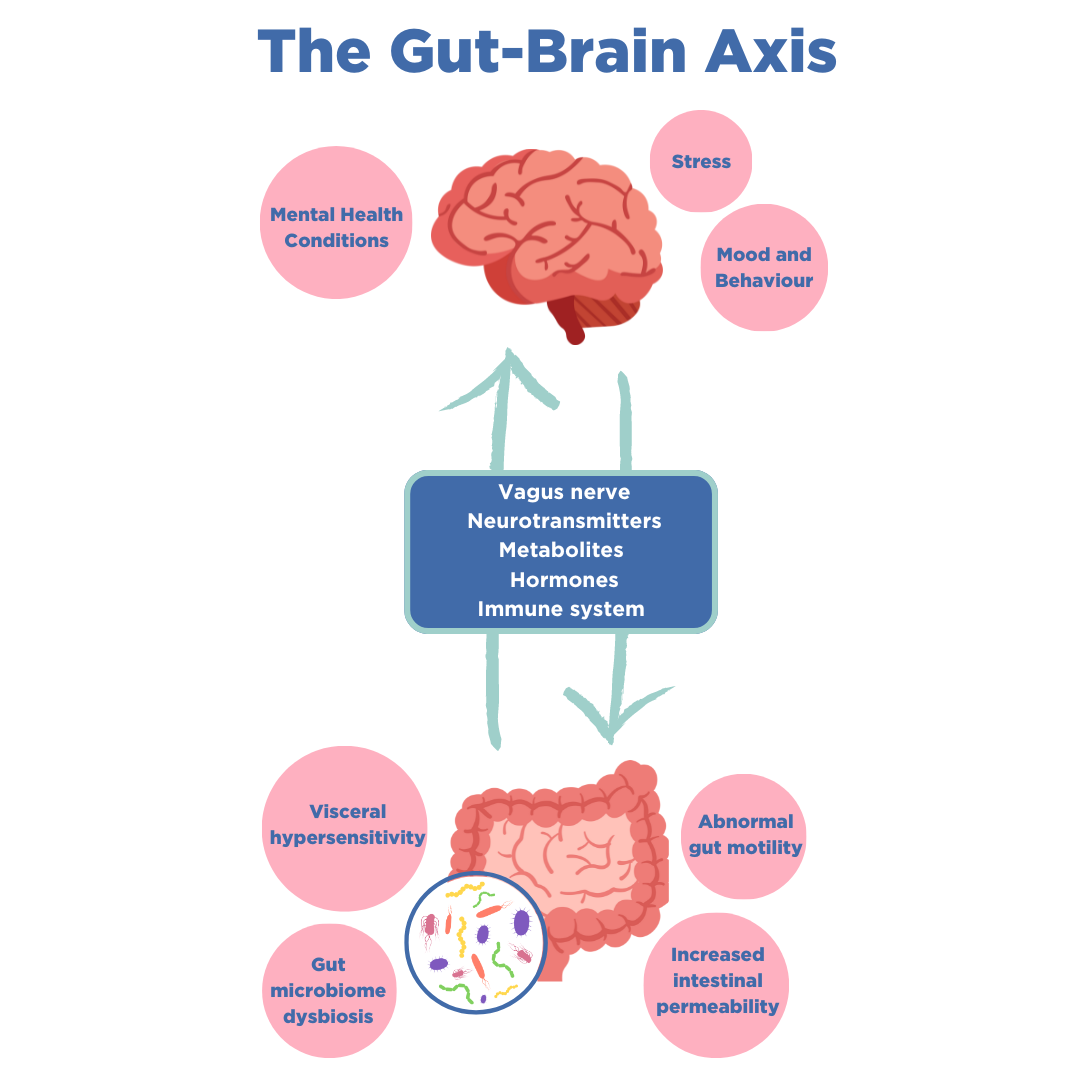

Both yoga and meditation focus on controlled breathing and have been associated with a number of positive health outcomes including reduced stress, anxiety, and depression in some people (4). But what does mental health have to do with gut conditions? Almost 85% of people with IBS also report symptoms of depression or anxiety (5). Furthermore, a Cambridge University study of over 50,000 people with IBS found that there may be similar genetic origins between IBS and mental health disorders, though environmental factors remain the strongest predictor of these conditions (6). This connection between the body and the mind lies in the gut-brain axis, a bi-directional communication that goes between the two systems. When we experience stress, signals travel between the gut and the brain, which can cause gut sensations like ‘butterflies in your stomach’. In moments of extreme stress or fear, this mechanism reduces blood flow to the gut, instead shifting energy and oxygen to key muscles and the brain to help us fight a threat or solve a problem urgently. However, this pathway can become overactive, stimulating uncomfortable gut symptoms with even the smallest of stressors. This is particularly common in IBS patients and explains why lowering stress through yoga or psychological therapy could improve physical symptoms (7).

Interestingly, the same Cambridge study found that people with IBS were significantly more likely to have had long-term or repeated courses of antibiotics during childhood compared to those without gut issues. This could impact the gut microbiome, which not only plays a role in the gut-brain axis but has recently been viewed as a central player in its control (8). Gut microbes can break down fibers from our diet to produce beneficial compounds that have many roles, potentially including mediating psychological stress (8,9) and mood. Due to the complex interactions between all these factors in determining gut health, it can be difficult to pinpoint the effects of practicing yoga.

Despite this, yoga presents another reason behind its potential to reduce gut symptoms; it’s a form of exercise. Keeping active has been found to keep worsening IBS symptoms at bay, where patients who exercised felt better than those who didn’t (10). Regular exercise has also been associated with higher gut microbiome diversity – an indicator of good gut health (11). Since exercise increases the circulation of blood around the body, this can also include the muscles of the abdominal area, especially when keeping the intensity lower. The gentle movements of yoga occupy that sweet spot that allows the body to mix relaxation with muscle stimulation and whole body stretches. Such movements may also physically massage the area around the gut, especially when working with twists and bends of the back and core. These could help reduce issues like constipation and slow gut motility which characterize conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Consistently practicing yoga could bring benefits to both mental and physical health, although the impact on gut health may differ depending on the person and how the addition fits into your life. Interested in how your gut microbiome responds to mindful activities? The OMED Health breath analyzer can show you levels of hydrogen and methane in your breath based on your daily meals, stress levels sleep, and more. These gases are produced by your gut bacteria and are used to diagnose certain food intolerances and SIBO.

If you would like to learn more about the science behind IBS, including causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments then download our free eBook. We bust common myths, explain the gut-brain axis in more detail, and provide guidance on what to do if you think you have IBS.

References

- Bonomini-Gnutzmann R, Plaza-Díaz J, Jorquera-Aguilera C, Rodríguez-Rodríguez A, Rodríguez-Rodríguez F. Effect of Intensity and Duration of Exercise on Gut Microbiota in Humans: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(15). doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159518

- Thakur ER, Shapiro JM, Wellington J, Sohl SJ, Danhauer SC, Moshiree B, et al. A systematic review of yoga for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. n/a(n/a):e14915. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14915

- Zaccaro A, Piarulli A, Laurino M, Garbella E, Menicucci D, Neri B, et al. How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2018 Sep 7;12:353. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00353

- Woodyard C. Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga and its ability to increase quality of life. International Journal of Yoga. 2011 Dec;4(2):49. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.85485

- Kawoos Y, Wani ZA, Kadla SA, Shah IA, Hussain A, Dar MM, et al. Psychiatric Co-morbidity in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome at a Tertiary Care Center in Northern India. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017 Oct;23(4):555–60. doi: 10.5056/jnm16166

- Eijsbouts C, Zheng T, Kennedy NA, Bonfiglio F, Anderson CA, Moutsianas L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of 53,400 people with irritable bowel syndrome highlights shared genetic pathways with mood and anxiety disorders. Nat Genet. 2021 Nov;53(11):1543–52. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00950-8

- Banerjee D, Bhatt S, Chatterjee S, Sharma R. IDDF2019-ABS-0189 Yoga-enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy (Y-CBT) versus rifamixin-probiotic sequential treatment for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a randomised clinical trial. Gut. 2019 Jun 1;68(Suppl 1):A100–A100. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-IDDFAbstracts.188

- Foster JA, Rinaman L, Cryan JF. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiology of Stress. 2017 Dec 1;7:124–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.03.001

- Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Regulation of the stress response by the gut microbiota: Implications for psychoneuroendocrinology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012 Sep 1;37(9):1369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.03.007

- Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 May;106(5):915–22. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.480

- Clauss M, Gérard P, Mosca A, Leclerc M. Interplay Between Exercise and Gut Microbiome in the Context of Human Health and Performance. Front Nutr. 2021 Jun 10;8. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.637010