The science behind what we eat, when we eat it, and how much we eat is a lot more complicated than just consuming the amount of calories our body needs to survive. In this blog, we are going to discuss what exactly it means to feel hungry, and what causes us to decide when to eat. Let’s tuck in!

What is hunger and ‘feeling full’?

Feeling hungry is a need for food, paired with a rumbling stomach. In more severe cases, the feeling of hunger can include mild light-headedness, dizziness, and nausea (1). A complex system of physical and hormonal signals causes what we know as hunger and involves many parts of the body, including the brain, nervous system, stomach, and intestinal tract. Hunger occurs because of biological changes in the body, which signals that you need to eat to maintain energy levels (1).

It is common to feel ‘stuffed’ after a big dinner, but when someone mentions dessert, you grow a second stomach! This isn’t true hunger, this is appetite. Appetite is simply the desire to eat and is often caused by emotional or environmental factors. For example, feeling stressed, sad, or bored can increase your appetite even when you are not hungry. It can also work the other way, and make you lose your appetite even when your body is hungry (2).

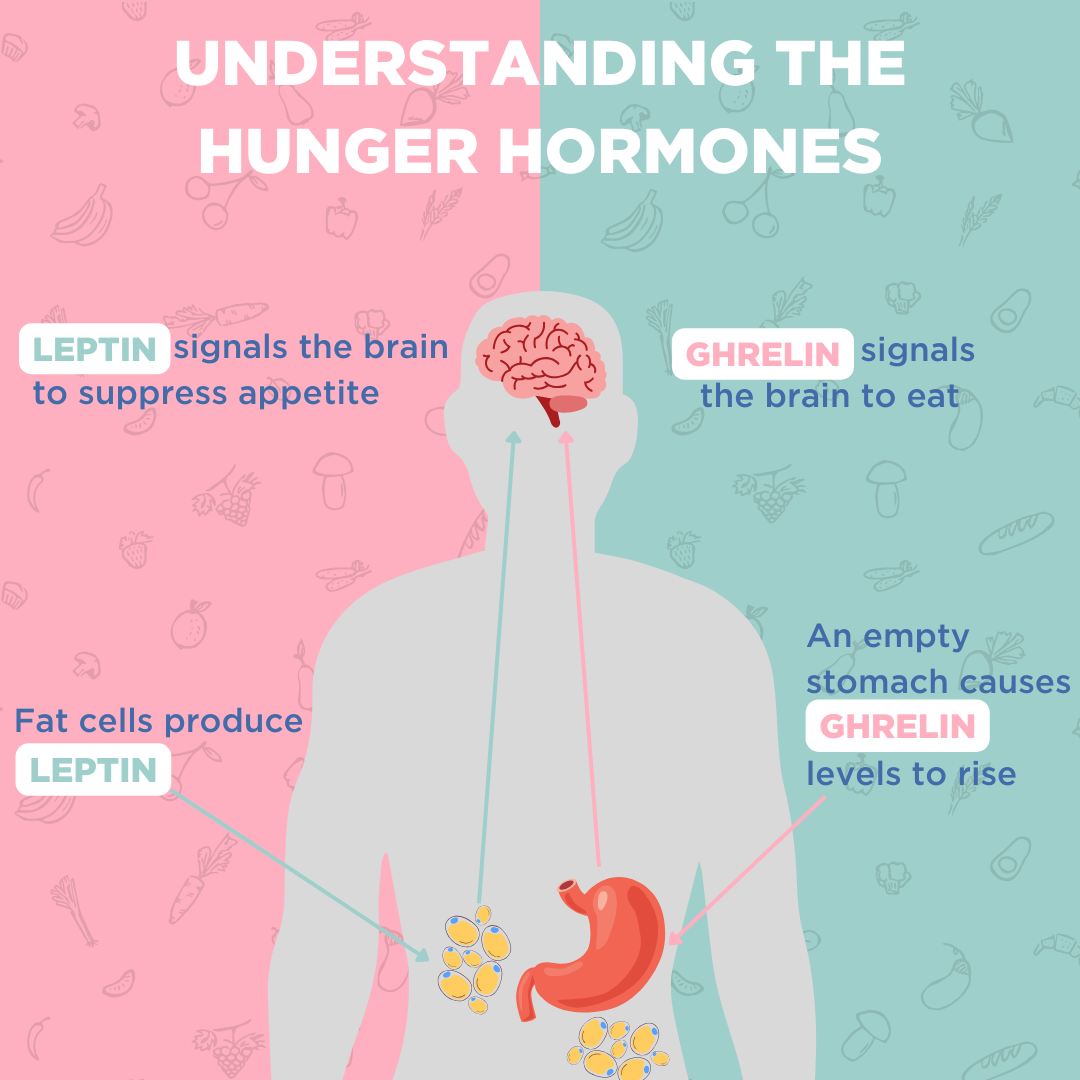

There are two main hormones involved in hunger signals – ghrelin and leptin. When you haven’t eaten for some time, the stomach produces ghrelin, which increases your appetite. This means that ghrelin levels are at their highest right before meals when your stomach is empty, and your blood sugar is low (3).

When you have eaten enough, fat cells produce leptin, which interacts with the brain and lets it know that you have enough calories in the body and that it is time to stop hunger signals (3). This process takes time, so when we eat too quickly we can end up eating more than we need which can lead to poor digestion and weight gain. Eating slowly results in better digestion and gives the body time to understand that it is ‘full’. Therefore, the link between the gut and the brain has a big impact on when we start and stop feeling hungry. This link is known as the gut-brain axis.

The gut-brain axis.

The gut-brain axis is a complex network of neural and chemical pathways that allow for communication between our gut and our brain. These pathways allow many different hormones and feelings to affect the gut and equally allow many of the changes in the gut and its environment to affect our mentality.

The gut can understand the nutritional status of our body after ingesting food and communicate this via the gut-brain axis to the brain, which regulates our food intake and maintains our metabolism. The vagus nerve is one of the biggest nerves connecting our gut and our brain and it can send signals in both directions (4).

The microbes that live in our gut (known as the gut microbiome) can also make other chemicals that affect the brain. For example, these microbes produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) after digesting fiber, and these SCFAs can reduce appetite (5).

Have you ever felt emotional when hungry, known as ‘hangry’? This is another example of how the gut and the brain are connected. Studies have found a link between low blood glucose and not being able to regulate feelings and emotions. Therefore, when your blood glucose levels are low because you haven’t eaten and feel hungry, this can cause you to feel ‘hangry’ until you eat and raise those blood glucose levels back up (6)!

Some digestive conditions can cause a loss of appetite. You still need to eat to get enough nutrients, but these conditions can cause a reduction in the desire to do so. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) for example can affect our appetite through horrible symptoms – such as abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhoea (7).

Trusting your gut.

Our body’s capacity to recognize signals to regulate how we make decisions about food is an impressive process.

Poor awareness of these signals can result in dysfunctional eating behaviors. For instance, when hunger signals are unable to trigger the motivation to eat, weight loss can occur and in severe cases lead to eating disorders. Alternatively, the inability to feel ‘full’ can dampen the reward of eating food and could result in over-eating and weight gain.

It is important to be aware and recognize if your body is not responding to hunger signals properly. If you have any concerns, contact a healthcare professional.

How can OMED Health help?

We know that it is important for individuals to gain insight into their gut health and have an accessible way of monitoring what is going on inside their bodies. We have developed the OMED Health Breath Analyzer and App, set to launch soon. This at-home breath testing device and paired app is a solution that enables the monitoring of compounds in the breath, alongside the tracking of relevant lifestyle factors that may contribute to your discomfort.

This includes your diet – our app features a diary where you can record your intake of food and any symptoms you are experiencing. Along with other important lifestyle factors, such as sleep, stress and exercise. By analyzing this data, patients can access personalized treatment plans and ongoing monitoring, meaning they can make well-informed decisions about their diet and gut health. Purchase your OMED Health Breath Analyzer now.

References.

- Davis J. Hunger, ghrelin and the gut. Brain Res. 2018 Aug 15;1693:154–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.01.024

- GIS. Hunger and Appetite [Internet]. Gastrointestinal Society. [cited 2024 Jan 25]. Available from: https://badgut.org/information-centre/a-z-digestive-topics/hunger-and-appetite/

- Klok MD, Jakobsdottir S, Drent ML. The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obes Rev. 2007;8(1):21–34. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x

- Li S, Liu M, Cao S, Liu B, Li D, Wang Z, et al. The Mechanism of the Gut-Brain Axis in Regulating Food Intake. Nutrients. 2023 Aug 25;15(17):3728. DOI: 10.3390/nu15173728

- Gupta A, Osadchiy V, Mayer EA. Brain–gut–microbiome interactions in obesity and food addiction. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Nov;17(11):655–72. DOI: 10.1038/s41575-020-0341-5

- MacCormack JK, Lindquist KA. Feeling hangry? When hunger is conceptualized as emotion. Emot Wash DC. 2019 Mar;19(2):301–19. DOI: 10.1037/emo0000422

- Jia W, Liang H, Wang L, Sun M, Xie X, Gao J, et al. Associations between Abnormal Eating Styles and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study among Medical School Students. Nutrients. 2022 Jan;14(14):2828. DOI: 10.3390/nu14142828