The intestinal wall is a semi-permeable barrier

You might have seen the term “leaky gut” around the internet, but what exactly does it mean? And can you test for a leaky gut at home?

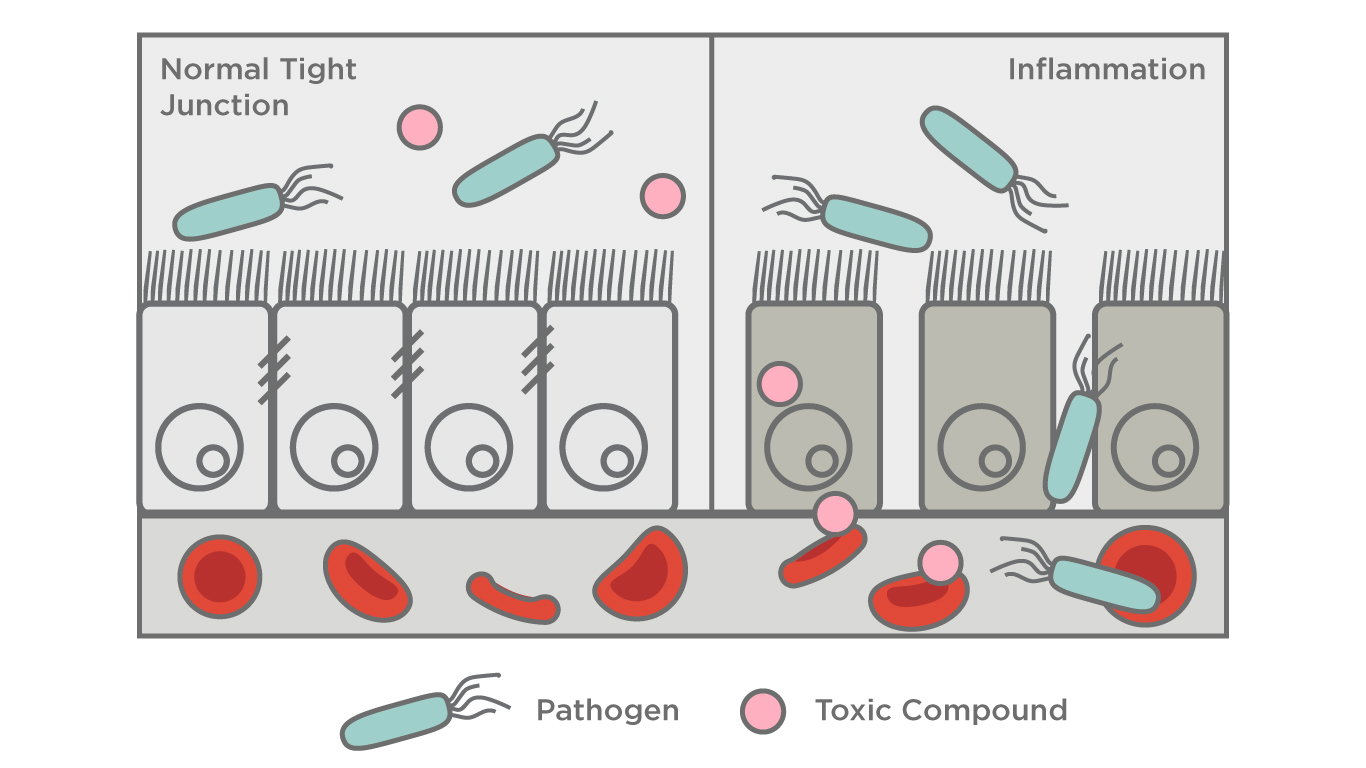

To start us off, to some degree, we all have a leaky gut! This is because our gut lining allows us to absorb water and essential nutrients from the food we eat through the intestine, and into our bodies to energize us. However, the gut lining also serves as a barrier to prevent larger unwanted molecules, and microbes from leaving the gut and entering deeper into the body. This sort of barrier is known as “semipermeable”, as it can let certain materials in, and keep others out. But what happens if our gut lining is compromised somehow, and unwanted molecules and potentially even microbes start to gain access to the rest of our body?

As it turns out, there are a few gastrointestinal disorders where an impaired barrier of the intestinal lining is known to play an important role; such as in celiac disease (1,2), and in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (3,4). In these conditions, the intestines are chronically inflamed, which wears down the intestinal barrier over time and allows pathogens, as well as pro-inflammatory and other toxic compounds to “leak” through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream.

This leaking can occur through two major mechanisms, either between the gaps of the cells of the intestinal wall, or through the cells themselves. The leaking of pro-inflammatory compounds through the intestinal lining into the bloodstream could explain why celiac disease and IBD both can have manifestations on the skin, such as chronic redness and rashes, despite being caused by an inflammatory process in the gastrointestinal tract (5,6). Interestingly, a marker for increased intestinal permeability has also been shown to be markedly elevated in people with rosacea (7). Supporting this hypothesis is the connection between rosacea and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) (8), which we have covered in a previous blog. A review of the literature found that increased intestinal permeability (aka leaky gut) was strongly associated with autoimmune diseases, diabetes food allergies/hypersensitivity, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and more (10).

What about a leaky gut in people without an underlying condition?

The principle behind the broader use of this term is the may have an impaired intestinal barrier that could be playing a role in a broader range of disease states, as well as potentially impacting our general health and well-being.

However, at present, there isn’t enough evidence to confidently conclude that common everyday factors such as stress, and diet can lead to a leaky gut in the absence of an underlying disease. This is because our gut has an amazing ability to heal itself, and the gut lining (known as the epithelium) regenerates itself approximately once a week. Demonstrating this, most people with celiac disease with a chronically inflamed gut can still recover over a few months to a few years upon adherence to a gluten-free diet (9). As the known causes of increased intestinal permeability like celiac disease and IBD involve a continuous breakdown of the intestinal lining and inflammation over long periods of time, it is unknown whether under normal conditions the lining can be damaged enough for it to begin to leak.

If you are experiencing chronic digestive symptoms such as bloating, abdominal pain, or changes to your bowel habits, it is important to contact your doctor to check that you aren’t suffering from conditions such as celiac, or IBD. However, in the absence of a clear diagnosis, these symptoms can be frustrating and life-limiting and can often lead people towards finding a simple explanation for them, of which “leaky gut” has emerged in the mainstream as a potential answer. It is important to note that it is thought that ongoing, chronic inflammation is needed to result in increased intestinal permeability, and your doctor can help you sort through the possible causes of your specific symptoms.

In the meantime, there are many ways to support your general gut health to alleviate uncomfortable digestive symptoms. This includes some easy modifications to your diet, and making sure that you are getting enough regular exercise and sleep to support your overall well-being and mental health.

We have recently launched our at-home OMED Health Breath Analyzer and paired App which can enable you to monitor hydrogen and methane levels in your breath alongside the tracking of relevant lifestyle factors that may contribute to your discomfort. By interpreting this data with the expertise of our network of experts, patients can access personalized treatment plans and ongoing monitoring, enabling them to make well-informed decisions about their gut health.

References

- Elburg RM van, Uil JJ, Mulder CJ, Heymans HS. Intestinal permeability in patients with coeliac disease and relatives of patients with coeliac disease. Gut. 1993 Mar 1;34(3):354–7. DOI: 10.1136/gut.34.3.354

- Fasano A, Not T, Wang W, Uzzau S, Berti I, Tommasini A, et al. Zonulin, a newly discovered modulator of intestinal permeability, and its expression in coeliac disease. The Lancet. 2000 Apr 29;355(9214):1518–9. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02169-3

- Wyatt J, Vogelsang H, Hübl W, Waldhoer T, Lochs H. Intestinal permeability and the prediction of relapse in Crohn’s disease. The Lancet. 1993 Jun 5;341(8858):1437–9. DOI: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90882-h

- Rojo ÓP, Román ALS, Arbizu EA, de la Hera Martínez A, Sevillano ER, Martínez AA. Serum lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in endotoxemic patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2007 Mar 1;13(3):269–77. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20019

- Bjarnason I, Marsh MN, Price A, Levi AJ, Peters TJ. Intestinal permeability in patients with coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis. Gut. 1985 Nov;26(11):1214–9. DOI: 10.1136/gut.26.11.1214

- He R, Zhao S, Cui M, Chen Y, Ma J, Li J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: basic characteristics, therapy, and potential pathophysiological associations. Front Immunol. 2023 Oct 26;14:1234535. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1234535

- Yüksel M, Ülfer G. Measurement of the serum zonulin levels in patients with acne rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Feb;33(1):389–92. DOI: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1757015

- Parodi A, Paolino S, Greco A, Drago F, Mansi C, Rebora A, et al. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Rosacea: Clinical Effectiveness of Its Eradication. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008 Jul 1;6(7):759–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.054

- Wahab PJ, Meijer JWR, Mulder CJJ. Histologic Follow-up of People With Celiac Disease on a Gluten-Free Diet: Slow and Incomplete Recovery. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2002 Sep 1;118(3):459–63. DOI: 10.1309/EVXT-851X-WHLC-RLX9

- Leech B, Schloss J, Steel A. Association between increased intestinal permeability and disease: A systematic review. Advances in Integrative Medicine. 2019 Mar 1;6(1):23–34. DOI:10.1016/j.aimed.2018.08.003