What is IMO?

IMO is characterized by the presence of abnormal and excessive methanogenic archaea in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, causing non-specific GI symptoms such as flatulence, abdominal discomfort, pain, and nausea. Contrary to its close relative SIBO, which often has diarrhoeal presentations, IMO is associated with constipation (1, 2). It is estimated that at least 33% of patients with unexplained GI symptoms or those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are affected by IMO (1).

Why does a high level of methane in the breath confirm IMO?

As hydrogen and methane gases are not endogenously produced by the human body but are the byproducts of microbial fermentation of undigested carbohydrates, they can serve as biomarkers for assessing methanogenic activity (3). Under normal physiological conditions, M. smithii, the most dominant methanogenic microbiome, plays a crucial role in the removal of hydrogen from fermented carbohydrates, which helps to enhance energy yield and ATP production of the host (4). With the hydrogen, M. smithii subsequently produces methane. When an overgrowth of M.smithii and other methanogens occurs, methane production increases, which correlates strongly with intestinal methanogen overgrowth (IMO) symptoms (5).

Receiving a diagnosis you’ve never heard of can be overwhelming. Intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth (IMO) is a condition that is often overlooked but can play a significant role in causing your gastrointestinal symptoms. In previous blogs, we provided an overview of IMO, covering its causes, diagnostics, and available treatments. In this one, we will guide you through the next steps after receiving a positive diagnosis.

What are my next steps?

As the pathophysiology and development of IMO can be multifaceted and complex, treatment involves targeting the underlying causes and addressing the symptoms. Here, we have largely broken down the next three steps.

Step 1: Identifying the underlying cause

Excess microbiome growth is usually limited by gastric acid, bile, peristalsis, and proteolytic digestive enzymes. However, there are conditions that impair these host defense mechanisms, fostering the overgrowth of microorganisms (6, 7):

| Anatomic abnormalities | Small intestinal diverticulosis, bowel structures, post-operative adhesions |

| Abnormal gastrointestinal motility | Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), post-radiation enteropathy, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus |

| Compromised immunity defense | Immunodeficiency disorders, reduced IgA production |

| Reduced gastric acid production | Proton pump inhibitor use, autoimmune gastritis |

| Medications that slow transit | Opioids, anticholinergics, dopamine agonists, calcium channel blockers |

These conditions promote the overgrowth of archaea and slow gut transit, providing more opportunity for bacterial or archaeal action. Unfortunately, these conditions are chronic and challenging to cure, with many treatments offering only modest improvements in IMO symptoms. In addition, a clear indication is necessary to determine if the patient requires any operative or invasive intervention due to the risks involved.

Step 2a: Addressing the symptoms – antimicrobials and antibiotics

Herbal antimicrobials can be used to treat SIBO to try and avoid the overuse of antibiotics, and to reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance. This includes probiotics and herbal remedies that include ginger and peppermint, which have been shown to be effective alternative SIBO treatments in some patients. Antibiotics, particularly the combination of rifaximin and neomycin, have been shown to be highly effective in alleviating GI symptoms and normalizing methane levels in lactulose breath tests. In a study evaluating the efficacy of the combination in patients with a positive methane breath test, 85% reported a clinical response. In comparison, 63% and 56% of patients reported improvement with neomycin and rifaximin monotherapy respectively.

In normalizing the breath tests, 87% of subjects in the combination therapy group eradicated methane, whereas only 28-33% of patients achieved methane elimination with single-antibiotic treatments. Subsequently, when patients in the rifaximin group were switched to combination therapy, 66% of patients eliminated methane from their breath (8).

Although metronidazole, clindamycin, and ampicillin have been studied, clinical trials have shown that their effectiveness is limited. The superior efficacy of rifaximin and neomycin is likely attributed to their unique pharmacokinetics – both are minimally absorbed in the GI tract, allowing their therapeutic actions to extend to the distal parts of the gut (9). However, in some regions, orally administered neomycin is unavailable due to its risk of nephrotoxicity, and irreversible auditory and vestibular ototoxicity. Consequently, rifaximin is used with other antibiotics (10, 11). It is essential to follow your doctor’s advice and adhere strictly to the prescribed treatment regimen to achieve optimal results and minimize the risk of complications.

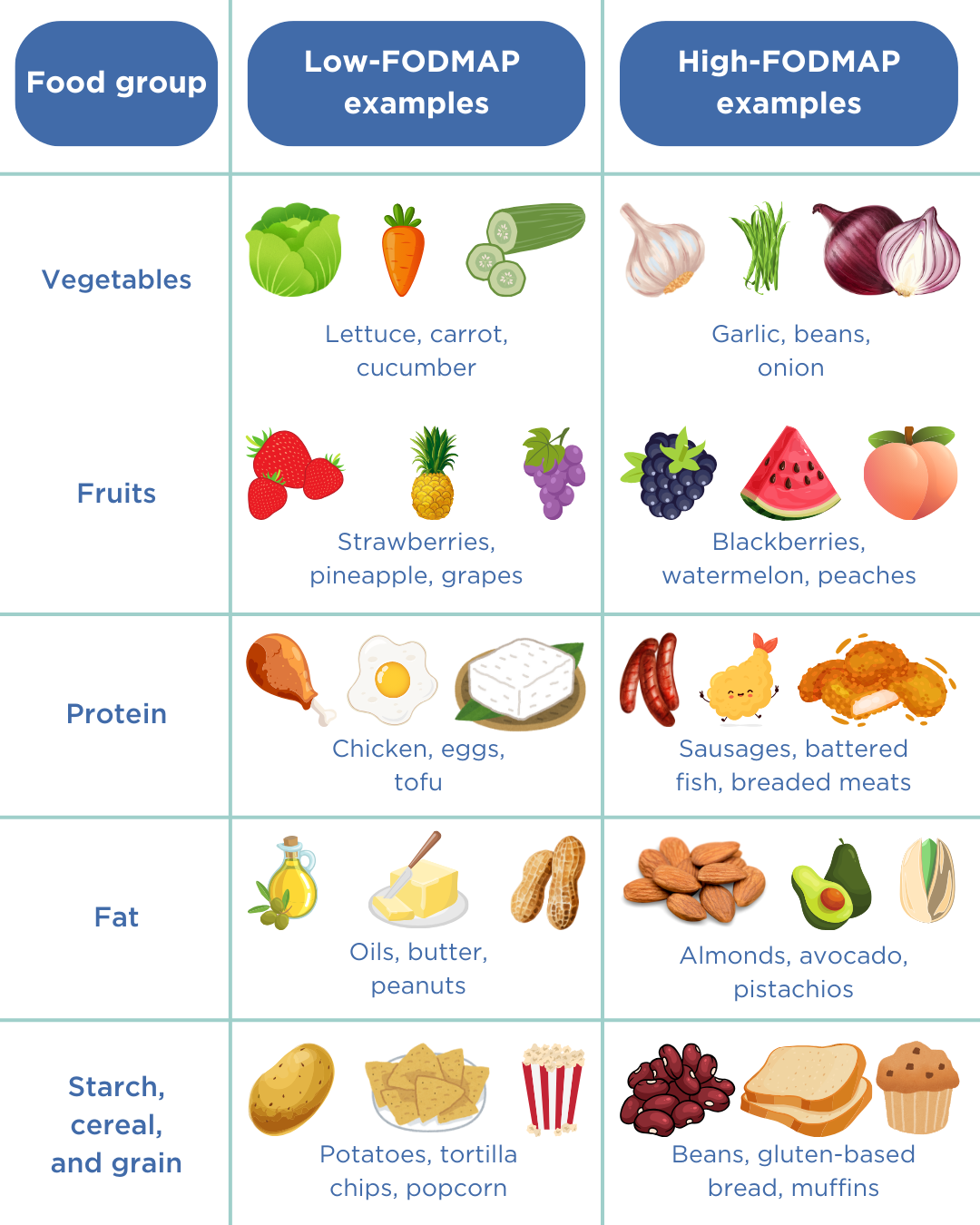

Step 2b: Addressing the symptoms – the low FODMAP diet

A favourable and viable strategy for reducing symptoms is the adoption of a low FODMAP (fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols) diet. FODMAPs are a group of carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and are prone to fermentation by the gut microbiome, leading to gas production and bloating. Limiting the intake of foods high in FODMAPs can limit the growth and proliferation of microorganisms (16).

- Foods high in FODMAP include certain dairy products (eg: milk, yoghurt and ice cream), wheat-based products (cereal, bread and crackers) and specific vegetables (eg: beans, lentils, onions and garlic).

- Foods low in FODMAP include eggs, meat, grains (eg: rice, quinoa and oats) and some vegetables (eg: eggplant, potatoes, tomatoes) (17).

The effects of a low-FODMAP diet exhibit considerable inter-patient variability, meaning that different individuals may experience varying responses to the same foods. Furthermore, a complete elimination of FODMAP-containing foods from the diet could lead to nutrient deficiencies. The low FODMAP approach is not only the exclusion of FODMAP-rich foods, but also a diagnostic tool to assess a patient’s tolerance to specific foods. The recommended approach is as follows (18):

- Patients should adhere to the low FODMAP diet as closely as possible for 4-6 weeks to determine if symptoms improve.

- After this initial period, it is crucial to reintroduce one FODMAP at a time, observing any symptoms over three days.

- With repeated testing, a balanced diet which incorporates certain high-FODMAP food is established.

Step 2c: Addressing the symptoms – the elemental diet

An alternative approach is the elemental diet – a meal-replacement formula with all the required nutrients, vitamins and minerals. As the formula can easily be absorbed without active digestion, the elemental diet meets the host’s nutritional requirements but simultaneously starves the excess microorganisms (12).

Studies by Pimentel et al. (2004) and Rezaie et al. (2024) found that a 2-week therapy was effective in normalising lactulose breath test in 58%-100% of IMO patients. In cases where methane was not entirely eliminated, many still showed a significant reduction in maximum exhaled methane levels and peak hydrogen rise (13, 14). However, elemental diet is associated with poor palatability and hence, compliance issues arise. As such, there is also a lack of long-term data (15).

It is worth noting that this diet can be difficult for patients to follow due to the high level of restrictiveness. Please make sure to speak with your doctor if you are considering this diet.

Step 3: Preventing remission

As treatment primarily focuses on alleviating symptoms, IMO can recur, particularly in patients with chronic conditions that predispose them to excessive microorganism growth. Managing IMO requires precision and timely intervention when excessive methanogen colonisation reoccurs. Hence, it is important to constantly monitor hydrogen and methane levels through breath tests to detect flare-ups and adjust treatment accordingly.

The OMED Health Breath Analyzer is a hand-held device that can provide real-time updates on hydrogen and methane levels in breath. When used in conjunction with the OMED Health app, which allows users to track lifestyle and dietary intake, patients can systematically monitor how these changes are affecting their GI symptoms. In cases where IMO has been resolved, we recommend routine testing for ongoing surveillance.

Conclusion

Treatment of IMO largely involves these three steps, but considerable inter-patient variability exists, necessitating the consideration of individual patient preferences. Tailoring a treatment regimen to align with these preferences is essential for achieving the most effective and sustainable outcomes.

References

- Rezaie A, Rao SSC. Chapter 15 – Intestinal bacterial, fungal, and methanogen overgrowth. In: Rao SSC, Parkman HP, McCallum RW, editors. Handbook of Gastrointestinal Motility and Disorders of Gut-Brain Interactions (Second Edition) [Internet]. Academic Press; 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. p. 205–21. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-13911-6.00015-3

- Mehravar S, Takakura W, Wang J, Pimentel M, Nasser J, Rezaie A. Symptom profile of patients with intestinal methanogen overgrowth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Aug 10;S1542-3565(24)00716-X. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.07.020

- https://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-resource/agip-protocol-for-hydrogen-methane-breath-testing

- Mohammadzadeh R, Mahnert A, Duller S, Moissl-Eichinger C. Archaeal key-residents within the human microbiome: characteristics, interactions and involvement in health and disease. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2022 Jun 1;67:102146. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2022.102146

- Yao CK, Tuck CJ. The clinical value of breath hydrogen testing. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2017;32(S1):20–2. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13689

- Sorathia SJ, Chippa V, Rivas JM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 28]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546634/

- Tansel A, Levinthal DJ. Understanding Our Tests: Hydrogen-Methane Breath Testing to Diagnose Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023 Feb 3;14(4):e00567. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000567

- Low K, Hwang L, Hua J, Zhu A, Morales W, Pimentel M. A combination of rifaximin and neomycin is most effective in treating irritable bowel syndrome patients with methane on lactulose breath test. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;44(8):547–50. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c64c90

- Algera JP, Törnblom H, Simrén M. Treatments targeting the luminal gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2022 Oct 1;66:102284. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102284

- Veirup N, Kyriakopoulos C. Neomycin. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560603/

- Neomycin sulfate | Drugs | BNF content published by NICE [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/neomycin-sulfate/

- Nasser J, Mehravar S, Pimentel M, Lim J, Mathur R, Boustany A, et al. Elemental Diet as a Therapeutic Modality: A Comprehensive Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Jul 13; doi: 10.1007/s10620-024-08543-1

- Pimentel M, Constantino T, Kong Y, Bajwa M, Rezaei A, Park S. A 14-Day Elemental Diet Is Highly Effective in Normalizing the Lactulose Breath Test. Dig Dis Sci. 2004 Jan 1;49(1):73–7. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000011605.43979.e1

- Rezaie A, Chang BW, Houser K, Mathur R, Brimberry D, Rashid M, et al. Mo1359 COMPLIANCE, SAFETY, AND EFFECT OF EXCLUSIVE PALATABLE ELEMENTAL DIET IN MICROBIAL OVERGROWTH: A PROSPECTIVE CLINICAL TRIAL. Gastroenterology. 2024 May 18;166(5, Supplement):S-1039. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(24)02863-4

- Achufusi TGO, Sharma A, Zamora EA, Manocha D. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Comprehensive Review of Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Methods. Cureus. 12(6):e8860. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8860

- FODMAP Diet: What You Need to Know [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/fodmap-diet-what-you-need-to-know

- nhs.uk [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) – Further help and support. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/irritable-bowel-syndrome-ibs/further-help-and-support/

- Starting the Low FODMAP Diet – Monash Fodmap [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 5]. Available from: https://www.monashfodmap.com/ibs-central/i-have-ibs/starting-the-low-fodmap-diet/