How can mold affect the gut?

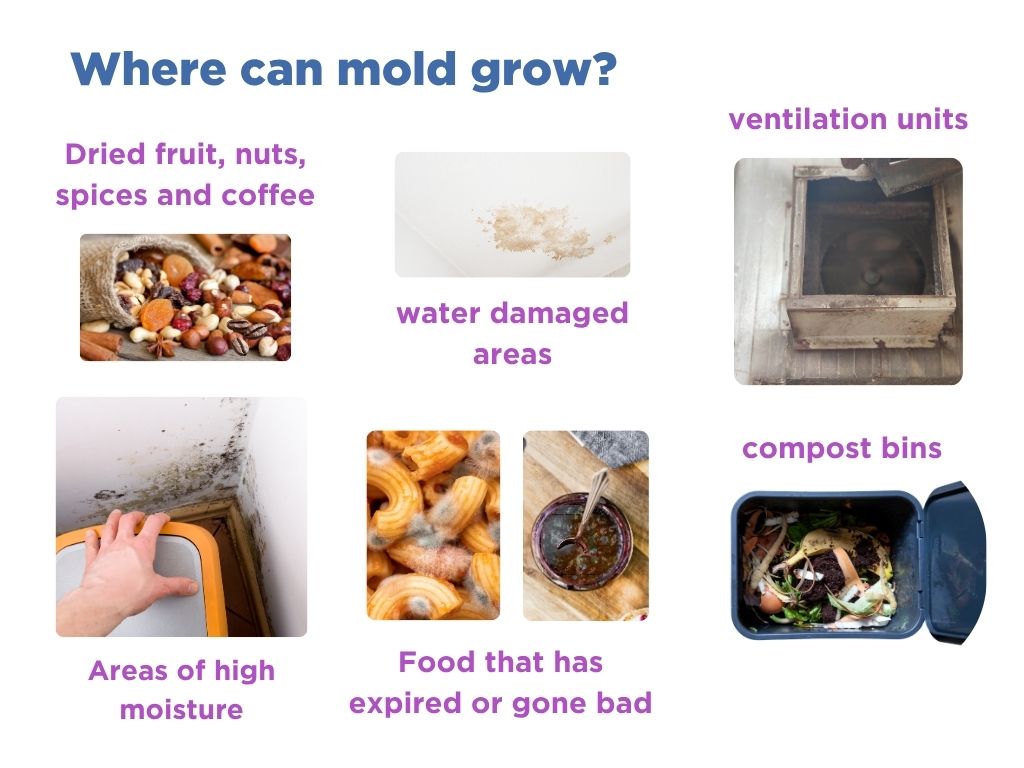

When trying to pinpoint the trigger for your digestive discomfort, it can be difficult to consider factors outside of the ‘norm.’ Mold exposure is well-known to damage our health, though it’s commonly associated with respiratory symptoms like sneezing or shortness of breath (1). However, researchers are increasingly finding that mold can have a significant impact on our gut health (2). You can be exposed to mold in several different fashions, including through the ingestion of foods, living or working in a damp environment, or touching molds through items such as a compost heap or even your pets. While not all mold is toxic, if mold-associated toxins enter your body, they can damage multiple organs, including your gut.

Mold can cause a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as exacerbate underlying gut issues. Common gut symptoms of mold exposure include (3):

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

These symptoms are triggered by tiny substances called mycotoxins; harmful metabolites released by certain types of molds. Small amounts of mycotoxins are commonly found around us, but chronic or high exposure can lead to illness and even death (2).

How do mycotoxins affect gut health?

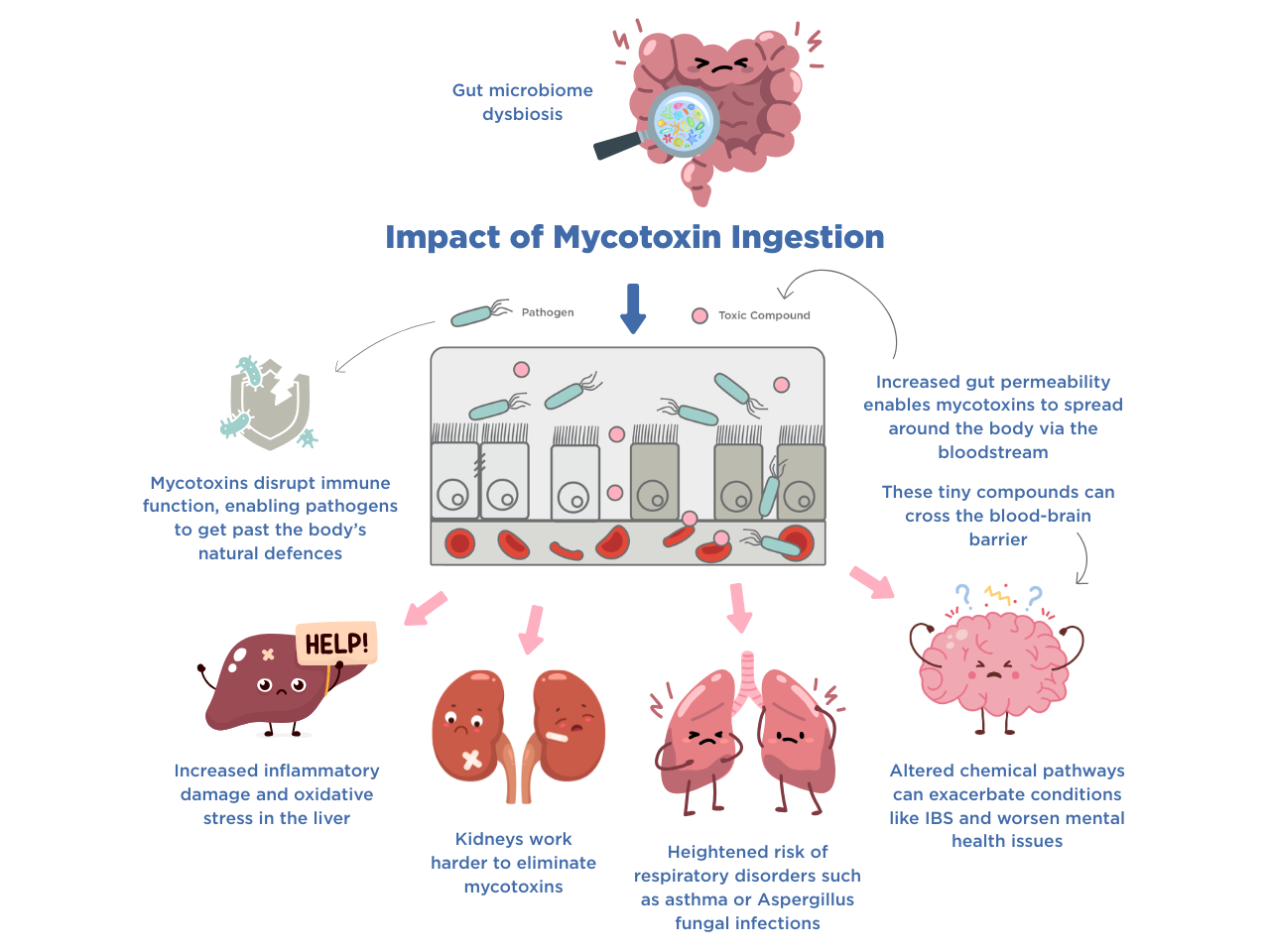

The gut is a complex system that relies on many working parts to keep us alive and healthy. The gut lining plays an important role, enabling the absorption of nutrients whilst acting as a barrier to prevent harmful substances from entering the bloodstream (4). If ingested, mycotoxins can damage the gut barrier and reduce nutrient absorption. They can cause difficult-to-reverse damage to the cells that line the intestinal wall, increasing its permeability and contributing to what is known as a leaky gut (3).

Once absorbed in the blood, mycotoxins can damage other areas of the body. Due to their small size, they can cross the blood-brain barrier, affecting the chemical pathways in our brains. Such disruptions can have a knock-on effect on the gut due to the gut-brain connection. Mycotoxins also cause inflammation and disrupt the immune system (5). For example, they can suppress and stimulate different processes of the immune system, disrupting the body’s ability to fight pathogens. This explains why eating mycotoxin contaminated food has been associated with an increased risk of infection, cancer, and immune deficiency (6).

The gut microbiome is a community of various microorganisms that inhabit the gut. This includes beneficial bacteria that help us digest our food and protect against harm. When the delicate balance of the gut microbiome is disrupted, this not only causes gastrointestinal symptoms, but can affect various aspects of our health including energy levels, mood, and mental clarity.

Some molds produce compounds with antimicrobial properties, meaning they can kill bacteria. In fact, an accidental mold growth prompted Alexander Flemming to discover Penicillin, an active agent of the Penicillium mold, leading to the creation of the first antibiotic (7).

Some mycotoxins, like antibiotics, can severely damage bacteria, causing them to die, upsetting the balance of the gut microbiome. However, some gut bacteria are able to break mycotoxins down into less harmful forms (4). Maintaining a robust microbiome can therefore prevent mycotoxins from damaging the gut. Unfortunately, an already disrupted gut microbiome fails to protect us from mycotoxin exposure, allowing for more damage to be incurred, which could lead to a negative spiral of worsening gut health.

Could my SIBO be caused by mold?

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a digestive issue that occurs when an abnormal number of bacteria colonize the small intestine, causing symptoms like bloating, diarrhea, and cramps. One of the key mechanisms that prevents bacteria from building up in the small intestine is the MMC (migrating motor complex).

The MMC is like a housekeeping system that gets activated when you’re fasting – i.e. during the time between meals. When active, the MMC causes the muscles of your small intestine to contract and relax. This helps move food, bacteria and other debris out of the small intestine and into colon, part of the large intestine where water is absorbed and where the majority of the gut microbiome is concentrated (3). Whilst there is usually no single cause behind the development of SIBO, MMC dysregulation is a known contributor (8).

But what does this have to do with mold? Mycotoxins have been shown to disrupt the MMC in animals by interfering with chemical signaling in the enteric nervous system. Known as the second brain, the enteric nervous system regulates gastrointestinal activities with the help of an estimated 200–500 million neurons which are located in the gut (9,10). When mycotoxins interfere with neuronal pathways in the gut and the brain, they could be contributing to gastrointestinal disorders and conditions like SIBO. Always speak to your doctor and get tested if you suspect that you may have SIBO.

What can I do to prevent the damaging effects of mycotoxins?

It is practically impossible to avoid mold, but there are a number of ways you can limit your exposure. Make sure you keep your home free of mold, ventilating rooms and not allowing molds to grow in warm, moist places. You should aim to keep the humidity in your home between 30 and 50% (11). If you find mold growing in your home, consult a professional to remove it as, once removed from surfaces, it can still be present in the air. Air purifiers can remove mold from the air, but not surface mold. You should use extractor fans in bathrooms and laundry rooms where mold is more likely to build up.

If you are regularly working on constructions sites or in other roles where you may be exposed to mold, consider wearing appropriate face coverings and protective clothing.

Store food well and avoid eating fresh produce that may have gone off or been contaminated during storage. Mycotoxins are more likely to be found in improperly stored grains, cereals, nuts, and fermented or processed foods, particularly under warm and humid conditions.

Due to the protective effect of a healthy gut microbiome, focus on maintaining a healthy gut through consistently eating dietary fiber and probiotics, exercise or gentle movement, as well as mental wellness. If you have been treated for gut conditions such as SIBO or IMO (intestinal methanogen overgrowth), focus on building up a strong and healthy gut microbiome to help protect you against any mycotoxin exposure you may encounter. Building a balanced gut will allow your gut to stop mycotoxins in their tracks before they can damage your body.

Each person has a unique response to mold exposure, meaning that the same level of mycotoxins could cause mild symptoms in one person, and impact someone else more severely. At OMED Health we do not offer any mold related testing solutions, however our gut health plans are designed to help you relieve your digestive symptoms.

With the help of the OMED Health Breath Analyzer, you can get a diagnosis and treatment plan for common gut disorders including SIBO. The device monitors the levels of hydrogen and methane in your breath, which are microbial metabolites. High levels are linked to microbial overgrowth in the small intestine. The OMED Health App allows you to discover how your symptoms and lifestyle factors may link to the activity of your gut microbiome. Get doctor-led plans and support by signing up today.

References:

- Platt SD, Martin CJ, Hunt SM, Lewis CW. Damp housing, mould growth, and symptomatic health state. 1989 Jun 24 [cited 2025 Jun 10]; https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.298.6689.1673

- Liew WPP, Mohd-Redzwan S. Mycotoxin: Its Impact on Gut Health and Microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018 Feb 26;8:60. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00060

- Gonkowski S, Gajęcka M, Makowska K. Mycotoxins and the Enteric Nervous System. Toxins. 2020 Jul;12(7):461. doi: 10.3390/toxins12070461

- Li K, Wang S, Qu W, Ahmed AA, Enneb W, Obeidat MD, et al. Natural products for Gut-X axis: pharmacology, toxicology and microbiology in mycotoxin-caused diseases. Front Pharmacol [Internet]. 2024 Jun 19 [cited 2025 Jun 10];15. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1419844

- Kraft S, Buchenauer L, Polte T. Mold, Mycotoxins and a Dysregulated Immune System: A Combination of Concern? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021 Jan;22(22):12269. doi: 10.3390/ijms222212269

- Mycotoxins [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mycotoxins

- Gaynes R. The Discovery of Penicillin—New Insights After More Than 75 Years of Clinical Use. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 May;23(5):849–53. doi: 10.3201/eid2305.161556

- Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007 Feb;3(2):112–22. PMCID: PMC3099351

- Schneider S, Wright CM, Heuckeroth RO. Unexpected Roles for the Second Brain: Enteric Nervous System as Master Regulator of Bowel Function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019 Feb 10;81:235–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021317-121515

- Gershon MD. The enteric nervous system: a second brain. Hosp Pract (1995). 1999 Jul 15;34(7):31–2, 35–8, 41-42 passim. doi: 10.3810/hp.1999.07.153

- US EPA O. Mold Course Chapter 2: [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2025 Jun 10]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/mold/mold-course-chapter-2